During his lifetime, Krzysztof Penderecki was undoubtedly the most famous composer in Poland, and one of the best-known contemporary composers worldwide. Thanks to its use in film and TV, from The Shining to Twin Peaks, Penderecki’s music has been heard by more people than most other avant-garde composers. His 90th anniversary provides an opportunity to reassess his work: both an exploration of historical trauma, and an investigation into our basic conceptions of what constitutes music, noise, and sound.

Krzysztof Penderecki (1933–2020)

Beginning in the late 1950s, Penderecki burst onto the scene with dense, dissonant works using a method known as “sonorism”, emphasizing timbre and texture over harmony and melody. Works like Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima retain a raw, palpable power, their noise and volume emerging from the trauma of post-war history, in Poland and elsewhere. Penderecki became a countercultural figure, with works such as the St Luke Passion playing a politically subversive role in Poland.

But by the mid-70s he’d reinvented himself as a neo-Romantic composer of traditional forms – symphonies, requiems, concertos. Grand, serious and ambitious in a manner that resembles the unlikely influence of composers like Anton Bruckner, these works self-consciously engaged with big subjects: from Polish history and politics in the Polish Requiem, to the creation of the world itself in his operatic adaptation of Milton’s Paradise Lost.

What connects these two apparently very different aesthetics? To get some answers to this question, I spoke to music writer Tim Rutherford-Johnson, who wrote a thesis on Penderecki and has spent many years thinking about the composer’s music. Despite his fame – which extends from the counterculture to Hollywood cinema to classical concert halls worldwide – Penderecki remains an enigma, Rutherford-Johnson suggests.

“For a lot of avant-garde composers,” he says, “you can boil them down to one word. For John Cage, it’s chance. For Brian Ferneyhough, it’s complexity. I’m not sure what the one word for Penderecki would be. He shape-shifts so much that it is quite hard to describe his influence or his contribution in just one way. And I think that’s what makes him such an interesting figure.”

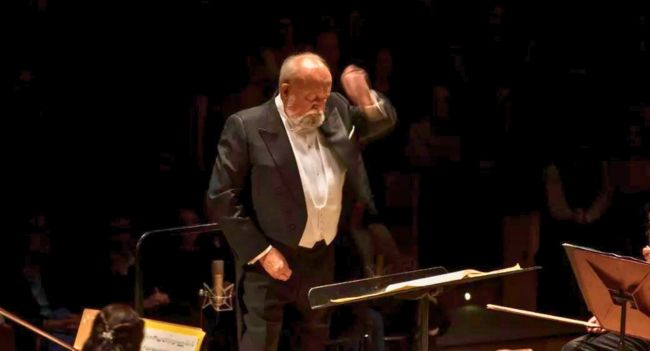

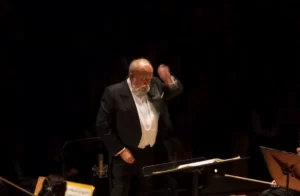

Krzysztof Penderecki conducts Polymorphia (1961) for 48 string instruments.

Penderecki’s work comes from a traumatic history: he grew up in Dębica, near the Ukrainian border, where he watched the Nazis construct a ghetto; one uncle was killed by the Nazis, one by the Soviets at Katyn. The town was largely Hasidic Jewish, with Catholics in a minority. Thirty of the forty pupils at Penderecki’s school were Jewish, all thirty suddenly disappearing when the ghetto was opened. The memory of this disappeared Jewish population, their music and culture, surfaces in a number of Penderecki’s later works.

After the war, Penderecki learned violin on an instrument his father purchased from a Russian soldier. Moving to Kraków in 1951, he studied at Jagiellonian University and the Kraków Academy of Music, where he was appointed to a teaching position in 1958.

This was an opportune time: a partial cultural thaw following the death of Stalin saw the music of the avant-garde pass through Polish musical culture like a breath of fresh air. In 1956, the Warsaw Autumn became the first avant-garde music festival in the Soviet bloc. Quickly gaining attention, the festival promoted work by Polish composers like Lutosławski, Gorecki and Penderecki, revealing an emergent Eastern European modernism distinct from that of the Darmstadt School.

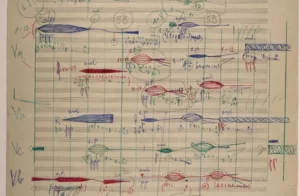

Sketch for Penderecki’s Polymorphia (1961)

Penderecki soon developed what he called a “sonoristic” style, signalled by Emanations, a work premiered at the Warsaw Autumn in 1959. Scored for two string orchestras tuned a minor second apart, Emanations used extended string techniques creating queasy, vertiginous ensemble textures: clusters, sound masses, like smears of paint on an Abstract Expressionist canvas.

Penderecki’s 1961 Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima is, Tim Rutherford-Johnson notes, essentially “a set of variations on a cluster”. The piece opens with fifty strings simultaneously playing their highest possible note. As it continues, Penderecki replaces melody, harmony and rhythm with a focus on timbre and texture that gives a raw, palpable quality to the music that can be shocking even today.

In pieces like Threnody, the musical avant-garde was a way to deal with the traumas of a history that could not yet be spoken about in official language. Penderecki recalled that he had in mind not only the atom bomb dropped on Japan, but “the destruction of the ghetto in my small native town of Dębica”.

Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima conducted by Krzysztof Urbański.

Yet the work speaks to history, not because it attempts to represent catastrophe, but because it embraces abstraction. As Rutherford-Johnson notes, Penderecki sought “to create musical shape in the almost total absence of any traditionally recognised musical elements, and of anything recognisably programmatic or representative.” In the post-Stalinist context, its very abstraction made it a protest and an act of defiance.

Yet Penderecki increasingly felt that the sonoristic style was limited. “The early experimental pieces were short”, he noted. “I was dreaming of writing a big oratorio, but I knew that with this kind of technique, I would never be able to write a longer piece.”

In 1963 he embarked on a new work commissioned for the 700th anniversary of the Münster Cathedral. Completed in 1966, the St Luke Passion is often taken as a turning point in Penderecki’s output. The piece integrates serialism, sonorism, Bachian oratorio structures and Renaissance polyphony. Largely atonal, it ends on a resplendent E-major triad. Politically, the piece fused two areas frowned on by the Polish authorities: religion and the avant-garde. The Polish premiere of the St Luke Passion was a phenomenon, attended by a crowd of 15,000 people.

Penderecki’s St Luke Passion conducted by Marzena Diakun.

For Penderecki, religion was something associated with persecution: from the horrors suffered by his Jewish neighbours during the war to the suppression of the church by the socialist government. The work encompassed not only “the passion of Christ, but also the passion of my generation… the cruelty of our own century, the martyrdom of Auschwitz.”

This theme also guided the 1968 opera The Devils of Loudon, leading to protests by the German Catholic church and the Vatican when it was staged in Stuttgart and Rome. The intersection of gender, sexuality and institutional religion remain potent and provocative. A TV production of Penderecki’s opera inspired Ken Russell’s own controversial take on the subject, The Devils.

Penderecki’s musical language was reaching a new density and complexity. Once more, he felt he had to change direction. Given advances in electronics, “we thought in the sixties that the orchestra might disappear”, he remarked. In the 70s, however, he became interested in the traditional forms and forces of oratorio, symphony, concerto and the possibilities of large-scale form.

Penderecki turned to the unlikely inspiration of Bruckner in works like Violin Concerto no. 1, written for Isaac Stern, and the opera Paradise Lost, written in commemoration of the US Bicentennial. “This music”, he wrote, “is more or less the synthesis. There are still elements from my early music because this was a very important period for me, this time of discovery. But my music is more mature.”

Though frequently commissioned by national and international bodies, perhaps the most important of these works, however, was an act of defiance to official institutions. Penderecki used his platform as Poland’s most famous living composer – and a relative immunity from state power – to speak out.

His 1980 Te Deum was commissioned by Solidarnosz for the opening of the Monument to the Fallen Shipyard Workers at the Gdańsk shipyard, ten years after government forces had opened fire on striking workers. Penderecki displayed his anti-government sentiments by including an excerpt from the Polish patriotic hymn, Boże coś Polskę (God Save Poland), which, since the early 19th century, had been used in defiance of Russian imperialism, and which had been sung spontaneously in the strikes that took place in Gdańsk that August.

Penderecki conducts

The Te Deum was followed in 1984 by the Polish Requiem, a work which, as Tim Rutherford-Johnson notes, “connects into so many threads of who he was. It feels like a piece that came from the heart and from necessity.” Referencing Verdi’s Requiem and its appeal for Italian reunification, alongside the international plea for peace of Britten’s War Requiem and further quotations of traditional Polish hymns.

By the time he wrote this work, Penderecki had moved into a renovated 18th-century manor house at Lusławice. Here, he built an elaborate park, home to over a thousand species of trees, and a maze. Referring to this garden, he remarked: “The search for order and harmony is associated with the feeling of collapse and apocalypses… I wander and roam entering my symbolic labyrinth.” The Adam Mickiewicz Institute have designed a digital tour of Penderecki’s garden – including its labyrinth – which they describe as a “kind of nonmusical artwork”.

Penderecki in his garden

It was in the labyrinth that Penderecki dreamed up what he called musica domestica – private works for more intimate forces – which are the real heart of his late music. Pieces such as the Third and Fourth String Quartets evoke many remembered melodies from Penderecki’s childhood. A Jewish melody that appears in the final, one-minute movement of the Fourth Quartet, stands out like a sudden interruption, a ghostly object in the midst of a texture that tries and fails to assimilate it. Penderecki spoke Yiddish as a boy. After the war, there was no one left to speak it to: all the Jewish inhabitants of his town had been massacred.

Penderecki’s music continues to be performed worldwide and to spark reflection amongst younger artists. As Barbara Schabowska, director of the Adam Mickiewicz Institute, remarks, he was “an artist… who left his mark on musicians – both those performing his works, and those inspired by him.” Penderecki’s music is ultimately one of unassimilated trauma, of clashes of opposites, of the depredations of institutional authority. It is music that insists that we face awkward truths, and that we hear difficult sounds; music that refuses to be assimilated, that insists on being heard.