The final five bars of the Prelude to Bach’s Second Cello Suite are often misinterpreted by performers, argues Mats Lidström, Leo Stern Professor of Cello at London’s Royal Academy of Music. Here he traces the source of the problem back to the ink- and paper-saving abbreviations of Baroque composers

Each performance of the Prelude from Bach’s Cello Suite in D minor BWV1008 reveals the cellist’s knowledge of 18th-century Baroque notation. Four bars before the concluding tonic chord, the energy and flow that have characterised the music up to that point are suddenly interrupted by a single dotted minim chord in each bar. This in itself puts great demands on the cellist’s bow-speed control – especially after having played almost two pages of mainly semiquavers. To sustain a chord across three strings for that amount of time, while also trying to maintain sound quality, is not only difficult, but makes little musical sense: the music resorts to practicalities, while expression and drama are lost rather than intensified. Graphically, these last few bars look strikingly different from the rest of the piece – more in the style of a sarabande – and are worth investigating.

In Bach’s time, paper was expensive and could also be difficult to come by, so wasting it was not an option. In one example Bach completes the last movement of a harpsichord concerto on the upper half of a page and follows it immediately with the beginning of a trio sonata in G minor – which he never completed. Added to the financial aspect was the fact that writing and copying music with pen and ink made for a tedious occupation, especially in the evenings when the lack of light slowed precision. Saving both paper and time was essential – hence composers’ use of abbreviations.

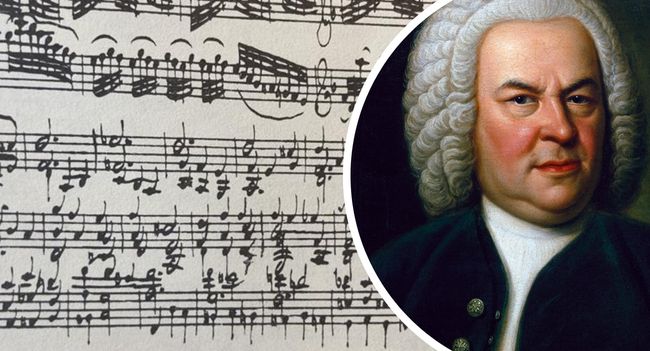

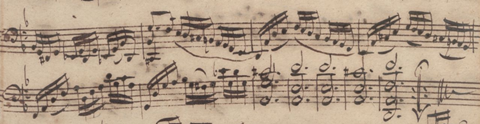

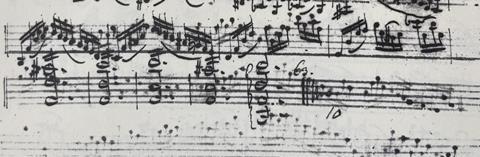

The technique used is this: a certain bar that the composer wants repeated, not necessarily in the same harmony but in the same shape or pattern, is fully written out. The next bar is written in a simplified way – a paper- and time-saving way – based on the pattern of the previous bar. The only thing that has changed is the harmony, while the design remains the same. In the case of the Prelude, the pattern and melodic design are shown by the composer in bar 58. The G minor key of bar 58 moves into a pedal point cadence beginning in bar 59 (V7), followed by a IC chord in bar 60. We then study the shape and melodic design of bar 58, subsequently applying these to bars 59–62, which lead up to the final D minor chord. Example 1 shows how this passage appears in the source copied by Bach’s wife, Anna Magdalena. Note how she copied bar 61 twice, instead of giving a second inversion of the tonic chord in bar 60; and compare this with the earliest surviving copy, prepared by Johann Peter Kellner in 1726 (example 2).

The information given here is not a suggestion for a variant or an alternative execution of the ‘original’. Instead, we are simply expected to follow Bach’s own pattern. This passage in the Prelude is one of many examples of a type of notation employed by composers, Mozart included, and is still in use even today.

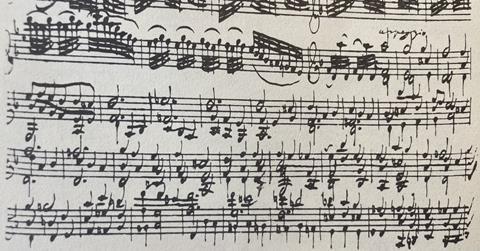

It would be helpful to us, three centuries on, to have additional instructions regarding the execution of the Prelude. In Bach’s case, words used for similar instances were ‘arpeggio’ or ‘segue’ – indeed, the former is found above bar 89 of the D minor Chaconne for solo violin (example 3). It saved Bach from having to write eight demisemiquavers for each beat throughout a substantial passage.

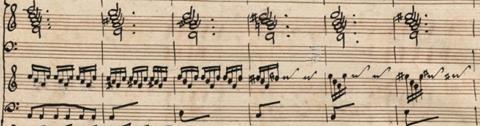

Another busy spot is found in Bach’s Concerto in A minor for four harpsichords (example 4). In each harpsichord part, instead of writing out every note, he shows the design in the first bar and then resorts to chords and other shorthand notations for the following bars to show the harmonic progression. Vivaldi saves paper and time in the last movement of his Concerto in A minor for two violins and leaves it to the performer to decide the pattern (example 5).

There might be as many as 50 different editions of the Bach Cello Suites in existence today. The majority are loyal to Anna Magdalena Bach’s handwritten copy, labelled Source A within the official research relating to these pieces. This means that the end of the D minor Prelude is mostly presented without a comment on Baroque notation. Source B (the Kellner copy) offers no further information; neither does Source C (the Westphal manuscript, prepared by two copyists and dating back to the second half of the 18th century, though brought to light in 1830).

But then there is Source D, prepared by an anonymous copyist, which quite astoundingly was offered for sale (along with other works by Bach) in 1799 by art and music dealer Johann Traeg in Vienna (example 6). This source adds two horizontal lines through the stem of each chord from bar 59, like tremolo lines, indicating thereby that the note values of bar 58 should continue.

Next is Source E and the first published edition of the Cello Suites, edited by Louis-Pierre Norblin (1781–1854), Auguste Franchomme’s teacher. According to the preface, Norblin discovered a manuscript of the Suites: ‘Après beaucoup de recherches en Allemagne. M. Norblin[…] enfin recueilli le fruit de sa persévérance, en faisant la découverte de ce précieux manuscrit’ (‘After a lot of research in Germany. Mr Norblin’s[…] perseverance was finally rewarded with the discovery of this precious manuscript’). It was published as Six Sonates ou Etudes in Paris in 1824. Underneath bar 59 is printed ‘Arpegio’, again an indication that some change is expected to the music as written (example 7).

Contrary to popular belief that the Suites were forgotten until Casals walked into the Casa Beethoven music shop on Las Ramblas, Barcelona, this music was known to many 19th-century cellists. Popper did not publish an edition, but we know from programme leaflets that he included the D minor Suite in some of his recital programmes. After Norblin’s edition, H.A. Probst in Leipzig published one in 1825; the word ‘arpeggio’ is used here. Friedrich Dotzauer’s edition appeared in 1826 with the chords only, no additional information; the same is the case in Alfred Dörffel’s edition from 1879 and in Hugo Becker’s of c.1911.

Friedrich Grützmacher published two editions. The one from around 1867 is advertised as ‘Original-Ausgabe’, an edition close to the original – though it’s still heavily edited. In his other version (1866), he reharmonises Bach’s text by adding double-stops or just changing it completely. He also transposes the Sixth Suite from D to G major. Still, the cover states that it is an ‘Edition originale’. In our Prelude, he does not use the chords, but writes out his own version as a continuation of bar 58 (example 8).

Brahms’s friend Robert Hausmann suggests ‘arpeggio’ in his 1898 edition. Julius Klengel in his edition from 1900 uses the chords, but also includes an ossia based on bar 58. Fernand Pollain (1879–1955) uses the chords in his 1918 edition, according to Source A (bar 60 corrected). But underneath the last bars he uses Bach’s pattern from bar 58, explaining: ‘Abrévation de copie très utisée chez Bach, et qui comporte la continuation du design mélodique réalisé ci-dessus’ (‘Abbreviation while copying, often used by Bach, continuing the melodic design shown previously’).

My own teacher Maja Vogl used Paul Bazelaire’s edition (1933), since she was a student of Bazelaire’s protégé Pierre Fournier. He does not show the chords, but chooses to complete the pattern for bars 59–62 according to bar 58 (example 9). We are all influenced by our teachers. With any luck, they have done proper research into what they teach us. Bach’s Cello Suites give the instrument a beautiful status – and maybe one day Sources X and F (as listed in Bärenreiter’s 2000 Urtext) will come to light: respectively the working copy and the fair copy in the hand of the composer.