Have you ever felt like there was never enough time in a piano lesson to cover everything? How can you fit it all in? Think about all it takes to educate and encourage a young person who aspires to enjoy playing music, and then on top of that try adding theory.

I’ve tried various ways of incorporating theory into piano lessons over the years, from extra group lessons to cramming in a little within private lessons. And admittedly, sometimes theory has gotten overlooked in favour of playing more music in the lesson. But here’s a new idea I’ve tried and it’s worked like a charm!

I originally got the idea from music history, from reading a little about Bach’s childhood.

J. S. Bach and what he got up to at night

The young Johann Sebastian Bach, orphaned at the age of 10, moved in with his eldest brother, Johann Christoph Bach. His older brother was a church organist and owned a good many manuscripts and he kept them locked in a cabinet.

The young Bach was forbidden from copying this music. Not only was Johann Christoph fairly strict (and likely didn’t want his younger brother handling his treasured manuscripts), but blank manuscript paper itself was quite expensive at that time and was used sparingly.

But the young Bach wanted very badly to learn more about music and to have some manuscripts of his own. He would rise from sleep in the middle of the night, reach his fingers into the locked cabinet and carefully remove pages of manuscript. By the light of the moon, he would copy the music onto his own pages.

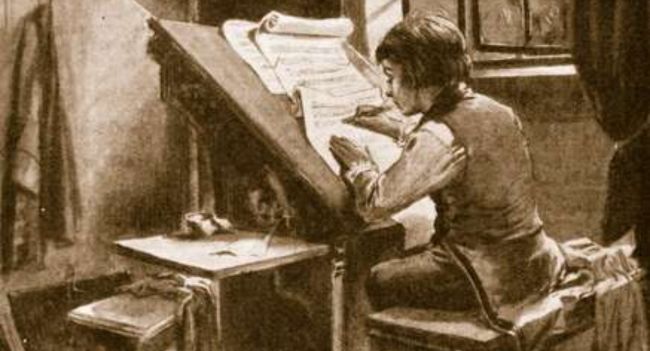

‘By the light of the moon he began his task’, (1907).The young Bach, despite having been forbidden to do so, copies out sheet music at night: ‘and by the light of the moon, which still streamed into the room, he feasted his eyes upon the pages before him. Then, taking his pen and some manuscript music-paper with which he had provided himself, he began his task of copying out the pieces contained in the book’. An episode from the life of German composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). From "Story-Lives of Great Musicians", by F.J. Rowbotham.

Eventually, his brother got wise to what young Bach was up to and caught him red-handed. It was then that the elder Bach acquiesced and agreed to teach him more about music.

With this story in mind, I tried a similar approach with my piano students.

(In case you’re imagining me locking up my print music, forbidding my students from copying it or asking them to awaken at night to do their homework, those aren’t the parts of the story that gave me inspiration.)

How to adapt Bach’s idea to piano lessons

The idea is very simple. I’ve asked my students to copy music by hand. My hypothesis is that they’ll learn a lot about music and theory and writing conventions (the rules of music notation), simply by copying good examples of actual music.

Most of my students also have theory books but we don’t always have time for theory. So, when time is short, I simply assign: “Theory – copy 2 measures.”

If you’re worried that children won’t learn much by copying music, consider how many details there are in the pieces they are currently learning. Those are the exact things they need to be covering in their theory.

Introducing students to copying

The first time I assign this, I give a brief telling of the story of Bach as a child. My students are then tasked with choosing two measures to copy from the repertoire they’re currently learning. They are to do their work at home and bring it to their next piano lesson.

My students have a printed dictation book with a small staff at the bottom of the page — exactly enough space in which to copy two measures of music.

The idea is to spend very little time on theory in the lesson and yet still include it in the lesson palette. Perhaps these are weeks when we are busy with repertoire or preparing a performance or on another focussed topic. So, I don’t go into detail on what ‘details’ they are to copy.

My primary goal is to observe the child. How much detail will they notice in the printed music? How accurately will they copy it?

In the example above, notice that the alignment is fairly good. What details would you point out for the student to fix? How much would you leave alone, or simply ask them to remember the next time they copy music?

It’s hilarious when a student chooses two measures of almost complete rest. It’s clear that they’ve tried to get away with as little effort as possible. But there’s something to be learned in measures of rests, too. Proper rest placement, for one, and a review of the difference between whole rests that hang and half rests that sit.

Most students choose music with lots of details, as you’ll see in the following examples.

When you compare their work to the original music they’ve copied, you’ll know what’s missing and when to gently encourage them to see details they’ve missed. The short discussion that you cultivate will be legitimate instruction in the rudiments of theory.

Lining it up

One of the first things students become aware of is how to line up the notes of the treble and bass clefs so that the music looks the way it sounds. Normally this develops with a little trial and error.

In the following example, the student has lined it up pretty well.

Notice that the forward repeat would need one more line, and that the bar line for the second copied measure is missing. This student also needs to remember to work in pencil, not pen. Can you spot the other tiny detail that’s missing?

With this kind of theory, I approach all corrections with a very casual and cheery tone of voice, saying things like, “Next time, watch for…” and I fill in the blank. Mostly, I’m just really glad they remembered to do it and appreciate the effort they’ve invested.

Noticing elements of basic notation

Before looking at my comments on the following example, take note of what feedback you’d give this student:

In the copied music above, the student has copied many details well. In your feedback, you’ll want to cover these points first.

- Good spacing of the left hand eighth notes

- Brace and first barline (often one or the other is missing)

- Clefs, time signature and dynamic mark p

But there are also some details that are missing:

- The whole rest in measure one

- Dynamic mark mp

- The barline at the end of the second measure

- And in measure 2, the 6/8 rhythms don’t line up

Extra picky things (that might bug piano teachers) that I may not mention at this stage are:

- The dynamic mark P should be written precisely above the first note

- The tempo marking

- The brace shouldn’t connect to the staff — it needs a bit of space. (This is picky and it will depend on the age of the child and how many other things I’m pointing out.)

The reason I choose to let some things slide is because kids are less likely to want to do this homework if it’s picked apart completely. I say just enough to let them know what kinds of things to look for so they’ll catch more details next time.

Noticing expression markings

In the following three images you’ll see the progression from the original print version of The Ninth Session (from Andrea Dow’s The Beethoven Sessions) to the first version of homework submitted, to the edited version after our short discussion.

It’s interesting to note above that on their own, this student copied the notes well but that the missing details were comprised of expressive marks.

This leads me to believe that integrated theory homework of this nature will help students to become more aware of all of the markings in their music, not just for theory and copying, but to boost how they learn and play their music.

The same student was much more attentive to details with the following two measures copied from the same piece. Can you spot the details that are still missing?

Note: Does this kind of copying breach copyright? If your students are already learning from purchased prints of the music and are copying only two measures at a time for educational purposes, no.

Integrated Applied Theory

Asking a student to copy real music they are currently learning integrates their theory into the rest of what they’re doing in piano lessons. And because it helps students connect theory with the pieces they are learning to play, it also makes their theory feel more relevant.

This adds a level of engagement that sets this kind of theory apart from workbook exercises that seem to be little more than math homework. Integrated theory heightens student awareness of the score and details that can actually give a boost to their playing.

As the teacher, it’s important to achieve just the right balance of addressing details and letting some things slide. As you notice your students becoming more attuned to notation and copying with greater accuracy, adjust and begin to expect more.

There is much to be learned from copying!

Speaking of hand-written music, here is a manuscript written by the adult J. S. Bach for a little inspiration.

Do you like this post and want more? In the side menu click “follow” to get notifications of my posts in your inbox.