Stuart Canin whips open the door to his Berkeley home and shakes my hand with the kind of solid clasp you’d expect from any lifelong violinist. While many in the Bay Area music scene know him as the celebrated former concertmaster of the San Francisco Symphony and first music director of the New Century Chamber Orchestra, history buffs may recognize him from his role in a unique performance right after World War II.

Canin, a Far Rockaway, Queens, New York native, was an army rifleman who thought to bring to war a cigar-box violin to “keep it in the fingers” while away from his famed teacher Ivan Galamian. Months later, he found himself on a balcony porch off a private home in Potsdam, Germany, with pianist Eugene List.

The mysterious task: Perform for President Truman. The date: July 17, 1945—what would later be known as day one of the Potsdam Conference.

I pick up a Brahms sonata now that I’ve played all my life and for some strange reason, I get a whole different look at it. You get, I think, closer to the composer’s intention as you mature. So, that’s how life goes. If you stay with it.

“Suddenly we heard automobile motors coming around the block and a bunch of limousines showed up and out of one stepped Joseph Stalin in his Marshall’s uniform,” Canin says, chuckling. “And Winston Churchill stepped out of the other. And Molotov, and Secretary of State Byrnes. Everybody who was ever on the front page of the New York Times came out of those cars and started into the house, and we said, ‘What’s this?’”

Hours later, the three titans—Truman, Churchill, and Stalin—sat on a small couch before the musicians. “And then Truman said, ‘Gentlemen, would you play something for us?’” Canin smiles as he recalls, “You could imagine, I was all of 19.”

Seventy-one years after the Potsdam concert, Canin was gearing up last November for a sold-out January Lincoln Center concert reenacting that exact program, to take place after the premiere of a documentary charting his role in the performance.

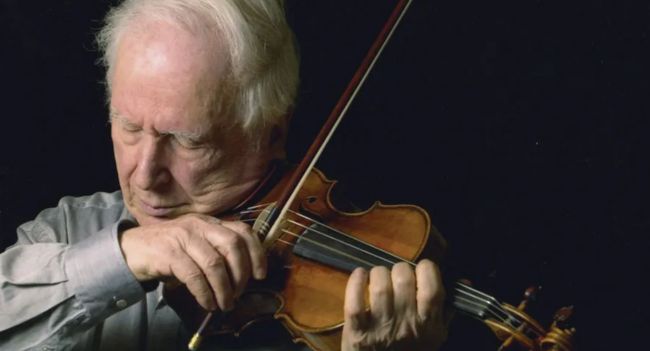

But Canin’s involvement in culturally significant moments hardly ended—or even began—with Potsdam. Canin, who, at the time of our interview looks forward to his 90th birthday in April, is warm and grounded as he glances back at his remarkable musical life.

Photo by Cristina Schreil

So, you picked up the violin at age five, correct?

My father actually picked it up. I didn’t know anything about the violin. [Laughs.] And he brought it home one holiday season and said, “Let’s try.” My father was absolutely nuts about the violin.

Did you take to it immediately?

At age seven, I remember playing a Vivaldi concerto with a little orchestra. My first teacher lived on 84th Street in Hammels near Rockaway Beach, so I used to go up there for lessons. He had a little orchestra and I played the Vivaldi A minor violin concerto at age seven for people—that’s pretty good. So, my father goes, “Hmm, maybe this has got a future.”

And how did that lead to you playing on the Fred Allen Radio Show at age ten?

The Fred Allen Show took out a little notice in the newspaper and said they were paying $75 for an appearance. And, since my father was making $25 a week [laughs], he said, “Well, let’s try for this!” So I went into New York and I played for a gentleman who was Fred’s assistant. His name was “Uncle” Jim Harkins. He was very well-known in the radio trade. I played a piece called Praeludium and Allegro by Fritz Kreisler and it took about five minutes. And when I finished he said, “You know, we’d love to have you on but our sponsor will not see us allowing a ten-year-old (which I was at that time) to have five minutes of national radio time playing this.” They watched the pennies like that. He said, “Do you have something shorter?”

I said, “I think I do.” So, I went home—I was practicing a piece called François Schubert’s The Bee—and I practiced until I got it down to about 45 seconds and I went back and I played it and Jim said, “Perfect.” And so on December 30, 1936, I performed on the Fred show. I got a very big hand on that round and Fred Allen said some nice things and then he said something to the effect that, “This ten-year-old boy can play The Bee so well and that 39-year-old comedian [Jack Benny] sounds like a she-wildcat defending her young when he plays.”

You have to have an intense love. That’s number one. If you just don’t care that much, you have to really go through heaven and hell to become part of that profession. And also, you have to practice. What else can I say?

You jumpstarted the rivalry.

The Benny-Allen feud, which became legendary!

As a kid, already at that point were you saying, ‘I would like to make a career doing this?’

No, no, no, no, no. I was practicing. My father was very level-headed . . . . At one point the NBC network called my dad and asked if he would like me to have a 15-minute radio show every week. My father said, “No, no, I want him to grow up as a normal kid.” It was really quite interesting.

When you turned 18, it was 1944. The war was starting to turn to the Allies’ favor.

And in October ’44 I received, what we used to say, “a letter from Franklin Roosevelt.”

And then everything changed?

I was drafted into the army and the only thing they found for me to do was become a rifleman. I was sent to Camp Blanding, which is in Florida, and trained there. This was November and suddenly in December the Battle of the Bulge happened, which shorted my training weeks from 17 to 13. In 13 weeks I became a full-fledged rifleman, capable of defending the United States. I was sent back home to take a vacation for a week before we went back into the army and then I was kind of worried about what would happen to my violin playing because nobody knows how long you’re going to be in the army. It depends on how the war is progressing. So I was sent overseas at the end of February, I believe, and I decided to take a violin—you know, just the cheapest fiddle I could find. What I will never forget, I walked up the gangplank of a troopship in New York harbor and I carried my barracks bag on one shoulder, my rifle on the other—you know you carry all this stuff with you—and my violin case, and when I walked up the gangplank my commanding officer says, “What are you gonna do with that?” pointing at the violin. And I said, “Well, you never know!” But really I just didn’t want to lose it. If I ever had any opportunity, [I wanted] to take it out and play. Just to keep it in the fingers. So on the troopship going across I played, I practiced. And in fact, I have confirmation of that because just a few years ago, maybe 15 years ago, I met someone who was on the same troopship. He said, “You know, I used to hear you playing.” Isn’t that funny? Somewhere in the hold!

Once in Europe, how did music still play a role in your life?

The war ended on May 8 and I was in Kassel, Germany. On May 10 I got orders giving me my next assignment.

And it turned out to be Paris. I said, “Wow that is something. Maybe I’ll be able to do something with my violin.” So they sent me back to Paris and the army was starting a soldier-show company. And I still remember these numbers: 6817th Soldier Show Company. They were collecting G.I.s who were all entertainers.

Did you collaborate with any other musicians there?

A pianist by the name of Eugene List, who was a very well-known American pianist. He was a wonderful pianist and my commanding officer said, “You know there are so many wounded soldiers in hospitals around Paris, it would be nice if you two guys got together and put together a program to play for the troops.”

How did you choose your program?

How did you choose your program?

First of all, the pieces needed to be short enough, because these guys were in bad shape. They had to have one idea—either very lively and jokey pieces or sweet songs that they could kind of relate to.

Playing together led to your being chosen to perform for Truman in Potsdam. How did that unfold?

One day our CO, commanding officer, came to us and said, “You know we just had word that Truman was coming over.” Mickey Rooney, Gene List, and myself, they flew us to Berlin because he was coming to Berlin—again nobody knew why—and we landed there and they drove us to Potsdam. They had a tent all set up for us.

So if you can imagine living in a tent with Mickey Rooney for a week! [Laughs.] So one day, we’re in the tent and my CO comes across and says, “You and Eugene get your shoes shined and your pants pressed and take a shave.”

Later, when Truman, Churchill, and Stalin were sitting there, how did it go?

I had put my violin behind the piano to just get it out of harm’s way and when I went behind the piano to get my fiddle, a Russian aide to Stalin, who was standing behind him, leaped across the room to see what I was taking out!

Out of this big, black case?

Exactly. So when I took the fiddle out he started to laugh and he went back.

What was the program?

One was the Praeludium and Allegro, which is the piece I played for the Fred Allen Show but was too long.

You redeemed it.

I redeemed it! Yes, I always say this piece is what started the Potsdam Conference.

What else did you play?

I played the slow movement of the Wieniawski D minor violin concerto, which is a lovely tune, and then another Kreisler piece, Tambourin Chinois, which is a short, sappy kind of piece with a Chinese overtone, and then played another famous piece of Kreisler’s, Liebesleid, and then finished with a piece called La Vida Breve, by Manuel de Falla. We felt that each piece had a little different color.

Were you nervous?

When I was getting my violin out I was terribly nervous because of my audience. Where else do you get three people like that as your sole audience? We went back three nights in a row to play for Truman and his aides.

You helped break up the tension before this big conference.

That’s what people think, that Truman thought that would be a good way to get started. One of my letters [home to my parents] said Truman’s aides said that [in concerts on the following evenings] he became suddenly more upbeat and seemed to be cheerful—and of course he had just gotten news that they had successfully exploded the atom bomb.

After the war, how did you start to build a career?

I got in touch with my teacher Ivan Galamian, he was a very well-known teacher at Juilliard, and I went to Juilliard for the next three years. The war broke us up for about two years. And of course, I had to get back in shape. I had started with him at age 12, so I had been with him for about six years before I went into the army.

So, I went back to Juilliard. You’re always wondering what to do with your life, when you’re a violinist, so I decided . . . to opt for a teaching position.

Well first, I got married—that was very important. My wife and I decided I did not want to hang around New York and just play on radio programs or commercials or whatever. So I took a position at the University of Iowa as a professor of violin and was first violinist of its Iowa String Quartet, and moved out of New York. I was there for three or four years at Iowa teaching, performing, playing concerts. You know, learning my trade.

And, we loved it.

What was interesting to you about chamber music?

I’ve always liked smaller groups—although that changed over the years—and one of the reasons is when you’re growing up and starting to play with other people, first you get to play with smaller groups. You play trios, string quartets, quintets. And that somehow was my grounding in music.

First of all, the music is extraordinarily beautiful. And fascinating, interesting, and just struck a chord (if I may say that) in me. I used to do a lot of chamber music when I was in New York, wondering what to do, at Juilliard.

When did you opt for less teaching and more playing?

In 1959, I saw that there was a competition called the Paganini International Violin Competition. So I thought I would try that out. I saw the repertoire and it looked good to me so I went and I won.

You earned a special status in addition to winning, right?

Yeah, I was the first American to win the Paganini Competition Prize. So anyway I did some big concertizing at that time based on the follow through of the big competition and then, you know, unless you are determined to be a traveling concert artist—Isaac Stern, Itzhak Perlman, that kind of thing—it never worked out that way. I’m not sure that I was ever cut out for that sort of thing.

A couple years later, you got an invitation to teach at Oberlin.

I taught there for five years. And I realized I wanted to get back to playing. There was a small orchestra being started by a well-known violinist called the Chamber Symphony of Philadelphia. So I was with this group for two years.

I was concertmaster, violin soloist with them, and we made a lot of records for RCA because they liked the idea of the small group that didn’t cost so much. But then I found out that there was an opening in San Francisco for concertmaster. I tried for it. I played for Seiji Ozawa, who was the conductor at that time, a Japanese phenomenon, and he offered me the position.

What was it like to be part of a symphony all of a sudden?

I had gotten a little bit of a desire when I was with this chamber symphony in Philadelphia. [In San Francisco], we were playing big repertoire; we were recording for RCA Victor, and so I began to see the professional musician’s life. Different from playing in a little string quartet with your friends. People paid money and came to hear us. We had big national tours. And then [I had] the idea: Maybe I should move on. I was always compelled to move on. You don’t want to get too comfortable in one spot.

You went on to work as a freelance musician in movie-soundtrack studios in Los Angeles for 12 years. At one point you were concertmaster for John Williams, and you played for the Jurassic Park and Forrest Gump soundtracks, right?

It was a lot of fun. It was much more lucrative. First of all, it was a for-profit organization and I had two kids in medical school at that time. [Laughs.] So, a lot of bucks I needed. And as concertmaster you have a special position in the orchestra. You’re always invited into the recording booth to listen to the playback.

You can hear the string area, see whether it’s sounding right. You’re a much bigger part here than in the symphonic world. So, we went to Los Angeles, in the studios, and then we came back and I was asked to start this New Century Chamber Orchestra, here, which is still going 20 years later.

So, I did that for seven years and then Kent Nagano, the conductor, was given the position of music director of the Los Angeles Opera and he and I knew each other very well. I had helped him out at the Berkeley Symphony a number of times, by playing concertmaster for him, and he said, how would you like to come back to Los Angeles? I went down for a year and I stayed ten.

You also worked with Paula Abdul.

On “Rush, Rush,” one of her big hits. I played the violin solo.

How would you say your diverse experiences over the years have molded you into the player you are today?

Well, without question, the varied forms of classical music that I’ve participated in, you know, unless you’re a complete dunderhead, you get ideas from everyone you’ve played with. Good, even bad people, you get ideas of “Don’t do that!”

So when I got into the symphony field, to meet great conductors all the time who have their own ideas, to get to know Nagano and [James] Conlon more intimately. Every little thing helps, you know? To this day I still listen to performances. You don’t copy, but you get ideas, if you understand what I’m saying. So, you always kind of stay fresh with music now. I pick up a Brahms sonata now that I’ve played all my life and for some strange reason, I get a whole different look at it. You get, I think, closer to the composer’s intention as you mature. So, that’s how life goes. If you stay with it.

Do you still play every day?

Oh yeah, I do. I play an hour and a half every day. I just gave a concert at Old First Church [on Sacramento Street in San Francisco] a couple of weeks ago and I have this documentary thing at Lincoln Center, so I have to play.

You mentioned being nervous before the Potsdam Conference concert. Have nerves ever been an issue for you otherwise?

I was nervous when I saw them. But, once I started to play, my focus was on playing the music and not on who I was playing for. So, that left me. To this day I’ve been pretty good about focusing on what I’m doing, rather than who I’m playing for.

Is that general advice you’d offer any player?

Well yeah, but you never know what the mind is going to do. Focus and also become sure enough of what you’re doing. I say people who know what they’re doing generally are not nervous. It’s people who have little weaknesses or little soft spots in their technique—that makes you nervous.

Looking back over your career, what do you see as the key moments, or the big risks that you’re happy you took?

Just starting to play the violin! [Laughs.] That was the biggie. In everything, that was the big stream, or the big river, and all the tributaries flowed from that.

Well, there are important things. Marrying my wife, who loves music more than I do, has been very helpful.

And then, winning the Paganini Competition was the thing. And, of course the Potsdam Conference. The whole thing is to try to distinguish yourself among the thousands of people playing the violin, and you can only do that by getting some sort of name in a good way.

Do you have a favorite piece or a favorite concert that you gave?

You know something, it’s like the old song: When I’m not near the girl I love, I love the girl I’m near.

Whatever music I’m playing. I have no favorite composers; you cannot play one composer forever. I’m also open to doing new music.

What advice would you give musicians with an up-and-coming career?

There’s always some forward thinking that you can do. First of all, you have to have an intense love. That’s number one. If you just don’t care that much, you have to really go through heaven and hell to become part of that profession.

And also, you have to practice. What else can I say?

I mean, I’m still, to this day, at 89, I’m still practicing, because there’s always something to learn. I would say you have to have the love for it. I mean, I’m not just talking about a fondness; I’m talking about a real desire or love.

Would you say playing over the years has kind of kept you young?

You don’t know why, but it keeps you alive. I mean, alive in the sense that your senses are alive—not just that you’re alive and walking . . . . Definitely it keeps you going and it’s just a great, great profession—if you can make your way in it. That’s the hard thing.

Do you think if your father had not handed you that violin—

I never would have played it.

Really?

Well, why would I have?

You don’t think you would be walking down the street and see a violin store and—

No. Well . . . I will never know.

Your 90th birthday is in April. Any big plans?

No, no. I’m telling my wife, I’m interested in 91. I don’t want anything big. That’s a finish. I don’t want a finish.