In the mid-16th century, Palestrina was appointed a member of the Papal Chapel, as a reward for his many compositions for the Catholic Church. This was a controversial move: the Pope at the time turned a blind eye to the fact that Palestrina was not in Holy Orders, and waived the rule that he must take a rather taxing entrance exam.

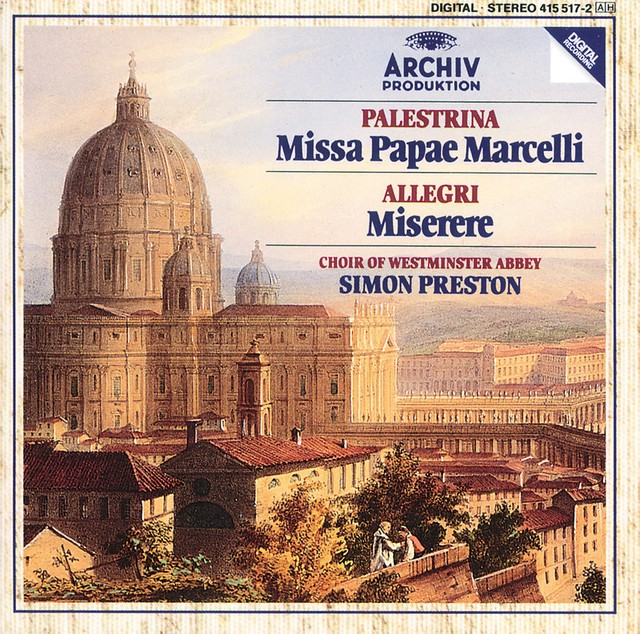

That, coupled with the fact that many existing members of the Papal Choir thought Palestrina’s voice wasn’t nearly as good as theirs, led to quite a storm of protest. A subsequent Pope adopted a more stringent approach and Palestrina was asked to leave the choir permanently, with only a small pension. The glorious Missa Papae Marcelli is Palestrina’s most famous and most beautiful mass, still regularly sung in Catholic churches the world over.

The range of Palestrina’s musical output was staggering: as well as masses, he composed secular madrigals, hymns, and a set of rather wonderful motets.

Palestrina, thanks also to the support of important ecclesiastical personalities, was active in important Roman musical chapels, was a member of the pontifical singers (even if the status of married man caused his removal) and Choir Director at the Cappella Giulia in San Pietro. He was also a Choir Director in San Giovanni in Laterano and Santa Maria Maggiore. The Treccani encyclopaedia summarizes the activity of this great genius: “The greatest Italian musician of the sixteenth century and leading exponent of the Roman Renaissance polyphonic school, Palestrina lived all his life in Rome, at the court of the popes, assuming the position of choirmaster at the main patriarchal basilicas for over forty years. His work was mainly linked to the production of Masses and liturgical music for pontifical celebrations.” It would be too long to remember all his works, but we can certainly name the monumental Missa Papae Marcelli for 6 voices, the summit of Renaissance polyphonic thought. Among the motets we would really be spoiled for choice, but we can mention the adoring Ego sum panis vivus (4 voices), the well-known Sicut Cervus (4 voices) and the equally famous Super flumina Babylonis (4 voices). The offertories are also very beautiful, among which we can mention Exaltabo te (5 voices).

Someone said that among the great musicians of the Roman school in the Renaissance, Orlando di Lasso composed for the emperor, Palestrina for the papal court and Tomas Luis de Victoria for God. This is true and false, in what concerns our Palestrina. It is true that his music matched perfectly the liturgies of the papal court, of the Holy Roman Church, but this did not mean they lacked those spiritual qualities that made them worthy of divine worship. Indeed, he was considered, and still is, a supreme model for those who compose music for the liturgy. His music is human in such a profound way as to transcend and rise up to God. It is not falsely spiritual music, far away, but music that resonates with true and authentic feelings and is thus very pleasing to God. In Palestrina’s music we find what was said in this famous passage of Saint Augustine: “And being thence admonished to return to myself, I entered even into my inward self, Thou being my Guide: and able I was, for Thou wert become my Helper. And I entered and beheld with the eye of my soul (such as it was), above the same eye of my soul, above my mind, the Light Unchangeable. Not this ordinary light, which all flesh may look upon, nor as it were a greater of the same kind, as though the brightness of this should be manifold brighter, and with its greatness take up all space. Not such was this light, but other, yea, far other from all these.”

In his music, Palestrina rejoins with what is authentically human in all of us and precisely for this reason is worthy of being in the presence of God who created us. He warns us against the dangers of false spirituality, of the spirit without flesh. In the music of Palestrina, as in the psalms, the man cries, adores, swears, shouts, rejoices. But he always does it with his eyes turned to God, the central point of the prospect of a whole existence.

But the God of Palestrina is not a vague, distant divinity. It is the God of the Catholic liturgy, who is worshiped through those texts and those ceremonies that come from a millenary tradition and that as such must be respected and handed down. Our composer understood that he had been given the highest task, to serve the divine cult with his music. Let us think for a moment of how this task is now degraded to an unseemly level, so that commercial music is allowed to dominate in churches. A time when we talk about “liturgical animation.” But are we the ones who give soul (‘anima’ is ‘soul’ in Italian and Latin languages) to the liturgy? What liturgy is it if it needs us to have a soul? It is the liturgy of man, the celebration of oneself, putting the human subject at the center of the universe. The liturgy is objective worship, that is, ultimately it does not depend on our work but worship is the voice of the Church as a mystery, not of individuals. This is why the music of Palestrina is truly the Church’s song, not the expression of a solitary genius. In him we all sing, we cry, we adore, we curse, we suffer before God.

He was regarded as the model of the Catholic composer. The Master (and Cardinal) Domenico Bartolucci, in an interview he gave many years ago to Sandro Magister, stated: “Palestrina is the first patriarch who understood what it means to make music; he sensed the need for contrapuntal writing bound by the text, alien to the complexity and canons of Flemish writing…. Music is art with a capital “A”. The sculpture has marble, architecture the building … You can only see the music through the eyes of the spirit, it gets inside you. And the Church has the merit of having cultivated it, of having given it its grammar and syntax. Music is the soul of the word that becomes art. Ultimately, it disposes you to discover and welcome the beauty of God. This is why, more than ever, today the Church must know how to regain it.” Here, we can make our own what Domenico Bartolucci had guessed in Palestrina: he was the one who knew how to go in search of the sacred “soul of the word” and transformed it into great art at the service of the liturgy and for the good of Christian people.

Did You Know?

Gregorio Allegri, composer of the popular choral work Miserere, was taught music by Palestrina.