Cellist Gregor Piatigorsky was larger than life, a giant of a man whose personality was gigantic, too. A warm, deeply expressive musician, Piatigorsky was possessed of a glorious low-register sound, great rhythmic gusto, and a musical imagination that led him to explore the subtlest shades of articulation. Tall enough that he made his instrument look like a toy (he could even pick it up and play it like a violin), Piatigorsky followed Emanuel Feuermann’s lead in taking cello technique to dazzling new heights. In addition to extraordinary general facility, his technical attributes included a violinistic ability to play octaves, and crackling up-bow and down-bow staccati. He was also an urbane and charismatic man who married a Rothschild, kept paintings by Picasso and Matisse in his studio, and could be as convincing with words as with his cello. For several decades in the mid-twentieth century, he was the cello’s greatest international star.

Born in Ukraine in 1903, Piatigorsky began studies in Moscow a few years before the Revolution. At a precocious fifteen, a year after the Revolution, he was appointed principal cellist of the Bolshoi Opera and member of the First State String Quartet. After being forbidden exit from Russia to study abroad, he escaped into Poland, then landed in Germany, where at twenty-one he was appointed principal of the Berlin Philharmonic under Furtwängler. Four years later, he opted to concentrate on a solo career, and in 1939 moved to the U.S., where he would give countless concerts in all manner of venues, grand and humble, including playing the first cello recital at the White House.

Along the way, Piatigorsky performed in piano trios with first Carl Flesch and Artur Schnabel, then Nathan Milstein and Vladimir Horowitz, and finally Jascha Heifetz and Artur Rubinstein. He played an indispensable role in the legendary Heifetz-Piatigorsky chamber-music concerts in Los Angeles and New York. In the area of new music, he commissioned the Walton Concerto, premiered the Sonata and Concerto of Hindemith, and made the first recording of the Shostakovich Sonata. Piatigorsky was also a devoted teacher, with positions at Curtis, UCLA, Tanglewood, Boston University, and USC. In his own playing, he was to a large extent self-taught, claiming as his greatest influence the great Russian bass, Feodor Chaliapin. An ever-searching musician, Piatigorsky believed that “the better you become… the music moves higher, so it becomes unreachable.”

Piatigorsky was a brilliant raconteur, with plenty of real-life stories to use as raw material for his imaginative powers. There was the time when, at fifteen, he objected to a proposed renaming of the First State String Quartet after Lenin (he preferred the name Beethoven) and soon found himself locked in an intense discussion of the subject with Lenin himself. Then, there was the daring escape into Poland, across a river, under Soviet gunfire, during the course of which he had to run through the water, cello held aloft, with a substantial soprano fellow escapee clinging to his back. Piatigorsky even wrote a novel, in English, long neglected and published only this year: Mr. Blok, about which his son Yoram has written: “I recognize Blok as a tormented fantasy of Papa, an original anti-hero bursting with ambition, flipping back and forth between exuberant inspiration and waves of sadness verging on despair…”

Piatigorsky died of lung cancer in 1976. But his musical imagination and wide emotional range can still be heard today in his many wonderful recordings. Perhaps greatest among his concerti was the Walton. A performance with Münch and the Boston Symphony is tonally enthralling throughout, ranging from full-throated eloquence to a kind of gentle musical caressing. Another highlight is Strauss’ Don Quixote, also recorded with Münch and Boston: When Strauss heard Piatigorsky play it in Berlin, he exclaimed, “I have finally heard my Don Quixote as I thought him to be.” Piatigorsky’s rich tone and ability to express over a wide emotional gamut are also perfectly suited to Bloch’s Schelomo (again with Münch and Boston).

Advertisement

The historic Shostakovich Sonata recording, with Valentin Pavlovsky at the piano, boasts some of Piatigorsky’s most compelling playing, alternately songful and sharply etched, hauntingly shaped in the Largo, and marvelously characterful in the Finale. The Brahms E minor Sonata with Rubinstein demonstrates his gorgeous low-register sound and ruminative patience, and in the Scherzo, more of his characterful rhythmic playing. Recordings from the Heifetz-Piatigorsky concerts boast myriad great cello moments. Among the most beautiful is the Andante of the Brahms C minor Piano Quartet, played with William Primrose and Jacob Lateiner.

Piatigorsky’s stupendous technique is shown off in his own twenty-fourth caprice-inspired “Variations on a Paganini theme,” recorded live with the NBC Symphony under Voorhees. Other recordings of shorter works include wonderfully subtle and sensitive Schumann Fantasiestücke, played with pianist Ralph Berkowitz, a bewitching and impassioned Granados “Orientale,” and a vibrantly soulful Sostenuto ed espressivo from Busoni’s Kleine Suite.

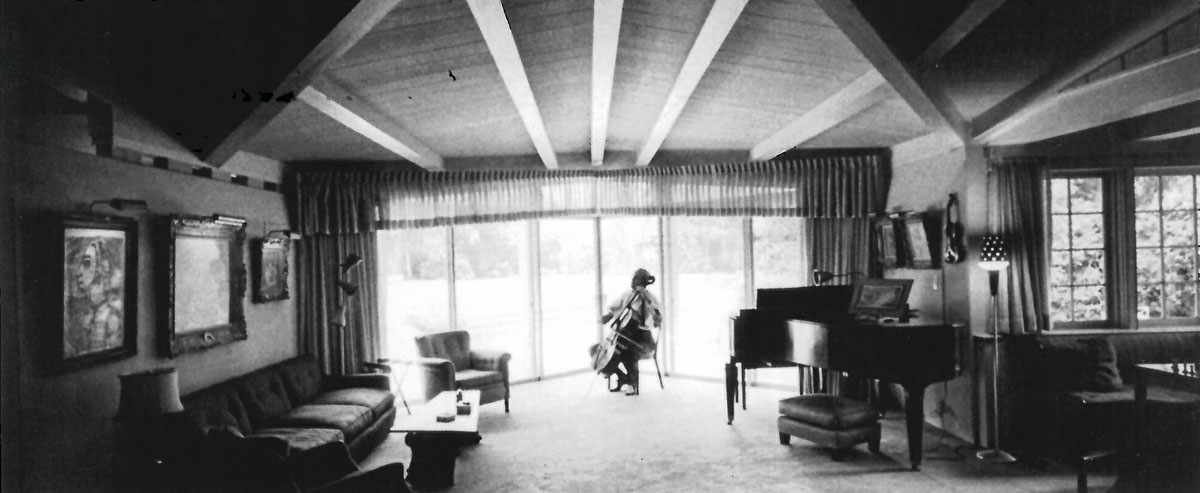

Gregor Piatigorsky in his home studio, Brentwood, California

(Piatigorsky Archives/Colburn School)

Saturday, May 21, Classical KUSC producer and well-known radio personality Gail Eichenthal will host a panel entitled Remembering Piatigorsky at the Piatigorsky International Cello Festival. At the free event, several of Gregor Piatigorsky’s former students, including Laurence Lesser, Mischa Maisky, Jeffrey Solow, and Raphael Wallfisch, will reminisce about their mentor and share archival images and video clips from the cellist’s life.

Recently, the KUSC radio program Thornton Center Stage featured an episode in tribute to Piatigorsky, whose teaching at USC Thornton influenced a generation of string musicians. The episode features performances and interviews with Thornton alumni, including Laurence Lesser, Michael Tilson Thomas, and Piatigorsky’s assistant and former Thornton faculty member, Nathaniel Rosen.

Gregor Piatigorsky had no small influence on the cultural life of Los Angeles. The following history of the cellist’s life and work in the city is drawn from an article in the Piatigorsky International Cello Festival program book, written by recent USC Thornton Musicology alum Keenan Reesor (MM ’10, DMA ’16) “Piatigorsky comes to Los Angeles”), with images and assistance from the Piatigorsky Archives at the Colburn School.

Three young Russian colleagues, 1930

Three young Russian colleagues, 1930Left to right: Nathan Milstein, Vladimir Horowitz, Gregor Piatigorsky (Piatigorsky Archives/Colburn School)

Piatigorsky’s success as a performer was only the beginning of a relationship with Los Angeles that grew deeper and more multifaceted as time went on. While its distance from such centers on the East Coast and in Europe was keenly felt, Los Angeles had an eager and increasingly well-funded audience for classical music. After his first performance, the Los Angeles Times named him as one of “three young Russian geniuses” whose performances had contributed to a “renaissance” of musical interest in Los Angeles, and in his second season, critic Edwin Schallert called Piatigorsky’s performance epoch-making.

“As far as cellists are concerned,” Schallert wrote, “this may be termed the Piatigorsky era. Piatigorsky has both rare nuance and singular depth, and he is technically remarkable.”

Piatigorsky’s journey to Los Angeles began with a dramatic sequence of events that entailed trudging across the Polish border with cello in hand in 1921, escaping police custody and deportation, and playing for food. By the early 1940’s, Piatigorsky had taken out naturalization papers and settled in Connecticut with his family. “I do not like to be called the young Russian cellist any more,” he told the Times in 1941. “. . . Please, if you speak of me, call me the ‘veteran American cellist.’ I like that much better. It makes me feel so proud!”

In 1949, Piatigorsky, now an American citizen, bought a home in the Westside Los Angeles suburb of Brentwood, where he would live for the rest of his life. Though originally a political refugee of the Soviet Union, his international success—to say nothing of his marriage to a Rothschild—placed him in a different social milieu than the broader émigré community in Los Angeles, which included numerous eminent European creative artists.

Gregor Piatigorsky, USC Master Class

Gregor Piatigorsky, USC Master ClassLeft to right: Nathaniel Rosen, Valerie Marshall, Gregor Piatigorsky, Denis Bortt (Piatigorsky Archives/Colburn School)

Like his neighbors Heifetz and Arthur Rubinstein, Piatigorsky made occasional appearances on film during this time, including the 1947 musical drama Carnegie Hall, and put his fame to local use. When financial distress threatened the existence of the Hollywood Bowl, Piatigorsky and conductor Alfred Wallenstein donated their services, and critic Albert Goldberg praised the newly unamplified venue, which “contributed an infinitely greater degree of intimacy and contact with the audience than was ever possible, and the result was an interpretation [of the Dvořák concerto] of uncommon eloquence.”

By the mid-1950s, Piatigorsky’s artistry had begun to assume civic importance. To his regular performances were added those at public events, such as the memorial service for Albert Einstein held at UCLA in May 1955. Piatigorsky began cultivate local musical talent by judging competitions, supporting the Los Angeles Junior Philharmonic, serving as president of the Young Musicians Foundation and more. Ready to devote a significant portion of his time and energy to regular teaching—which he considered it an integral part of his personal and artistic development—he joined the faculty at the University of Southern California in 1962.

What mattered most to him as a teacher was “how [his students] will use their art as human beings in a productive life,” and he considered it his duty as a teacher to be “a good man.” He said, “Without goodness, one cannot be right in any walk of life.” Piatigorsky’s commitment to his students remained utterly undiminished as his health gradually declined. “To his students he gave all of himself,” recalled his wife, Jacqueline. “When they came early in the morning I asked, ‘Will they be here for lunch?’ ‘No,’ he said. But they were still there for dinner.”

Piatigorsky died of cancer in his home on August 6, 1976. Piatigorsky belonged to the world, but no single place in the world has greater claim on him than Los Angeles.