Joseph Haydn conducting a string quartet

During his time in England, Haydn kept a personal diary called the “London Notebooks.” He recorded personal observations, scraps of poetry, Latin aphorisms, addresses and descriptions of places he visited, everyday gossip, and various anecdotes.

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 100 in G Major, “Military” (London Philharmonic Orchestra; Georg Solti, cond.)

As the Haydn biographer Albert Christoph Dies discovered, the “London Notebooks” also contained a couple of dozen letters in the English language. When Dies interviewed Haydn in his old age, the composer smiled and said “These letters are from an English widow in London who loved me; although she was getting on in age, she was still a beautiful and charming woman and I would have married her very easilye. if I had been free at the time”

Rebecca Schroeter

At that time, Haydn was still unhappily married to Anna Haydn, and the widow in question turns out to be Rebecca (Scott) Schroeter, an amateur musician and widow of the German composer Johann Samuel Schroeter. She lived in some comfort at No. 6 James Street, Buckingham Gate and she was looking for lessons from Haydn. “Mrs. Schroeter presents her compliments to Mr. Haydn, and informs him, she has just returned to town, and will be very happy to see him whenever it is convenient for him to give her a lesson.” Haydn accepted the invitation, and the “London Notebooks” contains 22 letters from Mrs. Schroeter to Haydn. These letters, however, are not preserved in the originals, but in copies made by Hayden.

Joseph Haydn: Keyboard Trio No. 24 in D Major (Beaux Arts Trio)

Rebecca was the daughter of a wealthy Scottish businessman living in London, and the family engaged Johann Schroeter as Rebecca’s music teacher. They fell in love, and against the wishes of her parents—who offered Johann a good deal of money to abandon the relationship—they got married. Once widowed, and in a curious repeat of history, Rebecca once again fell in love with her music teacher.

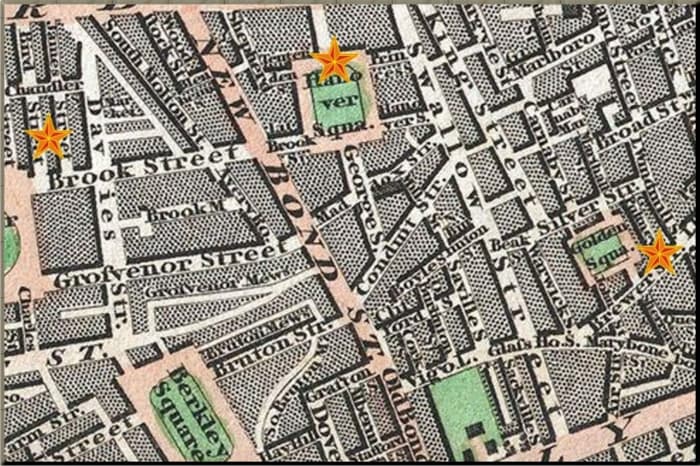

Map of London 1806 showing Rebecca Schroeter’s house in Hanover Square and Haydn’s rented lodgings

On 7 March 1792 Rebecca wrote to Franz Joseph, “My Dear. I was extremely sorry to part with you so suddenly last Night, our conversation was particularly interesting and I had a thousand things to say to you, my heart WAS and is full of TENDERNESS for you, but no language can express HALF the LOVE, and AFFECTION I feel for you, you are DEARER to me EVERY DAY of my life. … Oh how earnestly I wish to see you, I hope you will come to me tomorrow. I shall be happy to see you both in the Morning and the Evening. God Bless you my love, my thoughts, and best wishes ever accompany you, and I always am with the most sincere and invariable regard.”

Joseph Haydn: Keyboard Trio No. 25 in G Major “Gypsy Rondo” (Martha Argerich, piano; Renaud Capuçon, violin; Gautier Capuçon, cello)

Rebecca Schroeter was highly supportive of Haydn’s career, frequently telling him how much she appreciated his music. She writes on 19 April 1792, “My Dear, I was extremely sorry to hear this morning that you were indisposed, I am told you worked five hours at your Study’s yesterday, indeed MY Dear Love, I am afraid it will hurt you. Why should you who have already produced so many WONDERFUL and CHARMING compositions, still fatigue yourself with such close application.”

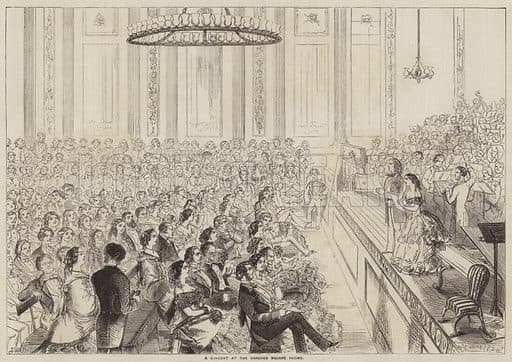

Concert at Hanover Square Room

The passionate affair continued until Haydn’s departure from England in 1792. Biographers were surprised that a love affair between the famous Haydn and a lady of London Society somehow managed to escape the gossip paparazzi of the day. It must have been conducted with a good deal of discretion, and Rebecca probably asked Haydn to return her letters prompting the composers to make copies. When Haydn returned to England in 1794 he rented lodgings a mere 10-minute walk from Schroeter’s residence, and it is believed that they continued their relationship. Shortly before Haydn departed permanently for his home in Austria in 1795, he wrote a set of three piano trios for Mrs. Schroeter. Although they would not see each other again after 1795, they surely remained friends and probably in touch.

It was an obituary in The Times that recalled the personal side of the story of Joseph Haydn that tends to become overwhelmed in the wealth of wonderful music he bequeathed to posterity.

Peter Hobday, who passed away last Saturday at the age of 82, was a well-known BBC broadcaster whose interests stretched way beyond the worlds of current affairs and finance in which he specialised on the air.

He’d tickle listeners to the Today programme on Radio 4 with tales of how the camellias were faring in his garden, and he wrote a book about one of classical music’s most prolific composers.

The Girl in Rose shone a spotlight on one of the women in Haydn’s life – an English widow by the name of Rebecca Schroeter.

Haydn, who spent many years managing the music for the aristocratic Esterházy family outside Vienna, was unhappily married.

His wife, Maria Anna Keller, had no interest in what he did. According to Haydn: A Creative Life in Music by husband and wife scholars Karl and Irene Geiringer (University of California Press) – Maria displayed an “utter lack of appreciation of his work”.

“Members of Haydn’s orchestra,” they note, “even said that Frau Haydn, out of pure mischief, liked to use the master’s manuscript scores as linings for her pastry or for curl papers.”

Cut off from the social life of the imperial capital, Haydn had a lengthy affair with one of the singers in the Esterházy company, Luigia Polzelli.

His music made him famous throughout Europe, especially in London – the nearest thing the 18th century had to a metropolis.

The English capital had evolved into the beating heart of the continent, assisted by the number of French who were there, having fled the Revolution of 1789. It was made for Haydn’s music.

Changing circumstances – Haydn’s principal patron had died – meant the composer was now free to travel. Paris was out of bounds because of the Revolution. So London it was.

Now nearly 60, Haydn had never even seen the sea before he set sail for England’s south coast.

“I stayed on deck during the whole crossing,” he recalled, “so as to gaze my fill at that mighty monster, the ocean.”

His arrival in London was big news, and led to an unusual introduction.

Rebecca, the daughter of a wealthy Scottish merchant, was the widow of prominent German pianist Johann Schroeter, who had been a regular in front of royal audiences.

She was well enough got to feel free to write to Haydn saying she would be very happy to see him whenever it was convenient for him to give her a lesson.

Though Haydn was 18 years older than his aspiring student, one thing led to another. Rebecca fell for her second man of music.

Haydn’s time in London was particularly productive. Among the many works completed there are the 12 so-called London Symphonies.

His chamber music from the period includes three piano trios specifically dedicated to Rebecca.

Twenty years later, shortly after the composer’s death in 1809, a biography referenced his recollection of letters “from an English widow in London who loved me (…) a beautiful and charming woman, whom I, if I had been single at the time, would very easily have married.”

It wasn’t just the audiences who couldn’t get enough of Joseph Haydn.