As musicians, our preoccupations in study and performance trend towards the compositional side of notoriety. When we think of the ‘greatest’ musicians, the names we tend to utter first are the composers: Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin, Brahms, Liszt, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev… This is not unreasonable, as without these masters of compositional craft we would not have their music. However, in consistently leaning on these gargantuan names, we tend to overlook the vast and storied history of the practitioners who have so brilliantly brought the works of these master creators to life. To be sure, many of these composers were prodigious instrumentalists in their own right, but once their time had past, it fell to the great interpreters to continue breathing life into their works and legacies. After all, a score is only a blueprint—it only comes to life when compiled into the ordered sound of performance.

So let’s narrow our query: Who are the greatest classical pianists of all time? Certainly, it’s a question doomed to plenty of subjective ping-pong, but let’s shell out some names we can safely assume will be on almost everybody’s lists. Conveniently, many of the composers mentioned above fall into the category. Bach was legendary for his keyboard prowess, astonishing both church and court with not only his abilities at literature interpretation, but also for his capabilities as an improviser. Mozart found himself pitted against fellow composer and pianist Muzio Clementi in a contest devised by the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II to determine the ultimate keyboard master (a contest Mozart is generally considered to have ‘won’ based on his choice of finesse over flash). And both Chopin and Liszt were by and large considered the greatest pianists of their times (as one might expect from two composers whose works were so ardently piano-centric.)

Let’s add a few more names to that list. In no particular order: Richter, Gould, Horowitz, Michelangeli, Schnabel, Arraú, Fischer, Cortot, Godowsky, Cliburn, Hofmann, Cziffra, Gilels, Schiff, Zimerman, Rubinstein, the other Rubinstein…

It’s quite a cast of characters, and they are all deserving of their accolades to some degree or another.

However, there is an egregious omission from both of these lists, one that, even in our time of increasing awareness and equalizing recognition, is all too easy to overlook:

Not a single woman is named among them.

It is a tragedy of the history of classical music that women have not been afforded the same time and support to foster their compositional prowess as men. Over the past five-hundred years there have been many, many women composers, and few have managed to impact the grand, venerated perception of identity at the core of classical music like their male counterparts. Make no mistake, this is not to say that female composers were not as good as their male peers, but that their works were almost never able to enter the realm of canon like the compositions of men due to lack of recognition and the societal norms that held music composition to be an exclusively “male” pursuit.

The world of classical piano, however, has much less an excuse for such exclusion. As we will see, while the fight for proper recognition for women in any professional role is never as easy as it is for men, the relationship between women and the keyboard has never been as taboo as with other instruments. By the time the walls of society started crack and more readily accept women as professional pianists in the middle of the 20th century, there was already a rich history of remarkable female performers and educators. In the world of classical piano, as with any profession, women still had to fight for their rightful regard, but at least the world of classical piano has seemed more readily willing to accept the evident talent and value of skilled female practitioners when it’s properly illuminated.

This is by no means a comprehensive list of every great female pianist, but rather a tailored introduction to some of the more notable female figures of the classical piano world. Throughout this article, we will loosely follow the paths and stories of the women of classical piano as they wound their way through the events and relevant areas of history. We encourage you to take a moment to listen to or watch the recordings included in this article, and to continue learning about these remarkable women of the classical piano through further study and investigation.

In the Beginning

We start in the days of knee-high socks and powdered wigs.

By and large, the centuries preceding the 1800’s were unfriendly to the idea of European, American, and Latin American women pursuing a career in music performance. Indeed, even up through the first half of the 20th century, the assumed role of women as housekeepers, child-tenders, and support staff was no less ingrained in the realm of music as it was any other social and professional arena. While notable instances existed, primarily amongst the likes of operatic singers and theatre performers, most of the female world was restricted to the narrow path of managing home and hearth, and partaking in socially acceptable leisure activities.

It would seem somewhat ironic then that the origins of the remarkable and fecund relationship between women and classical piano could be found in such an ostensibly fallow historical field, however that is exactly the case. As signifiers of wealth grew to include the time and means to produce music, the “appropriate” performance of music was to become a standard option of feminine activity, long before the piano was even invented. Relatively diminutive, gentle-in-volume keyboard instruments such as the clavichord, virginal, and spinet were considered ideally suited for the artful preoccupation of the feminine mind and body, and the ability to toss off a genteel minuet or prelude was considered nearly essential for any well-mannered lady of musical means. Fortunately, not unlike nature itself, the talents of women were not to be constrained by the insistent and ignorant fetters of Man, and it would not be long before the first female luminaries of the keyboard cast their light into history.

The prevalence of keyboard instruments in the houses of the well-to-do created a demand for teachers willing and able to foster the skills of budding young ladies. This could be quite a lucrative endeavor, and was very much so a standard manner of musical bread-winning by the time Mozart came onto the scene in the second half of the 18th century. By this time, it was far from unusual for particularly talented women to achieve a certain recognition in their regions for the quality of their playing, and in some cases that talent was enough to garner the coveted acknowledgment of renown teachers and musicians. Rose Cannabich (1764–1839), born into a musical family in Mannheim, Germany, received piano lessons from Mozart for five months between November of 1777 and March of 1778, and impressed the masterful young man so much that he dedicated his Piano Sonata No. 7 in C-Major to her. Slightly later, the English pianist Lucy Anderson (1797–1878) would graduate from lessons with composer and organist William Crotch to make a name for herself as the earliest female pianist to be involved with the concerts of London’s Philharmonic Society.

As the first decades of the 19th century progressed, the culture of home-raised female virtuosos would follow in the wake of blossoming Romantic sensibilities and dramatically evolving pianistic repertoire to include broader recognition and a deepening acceptance within less official circles of musical acclaim. It is here that we encounter the woman who would set the standard for the potential of female classical pianists, and who would go down in history as the grand matriarch of classical piano.

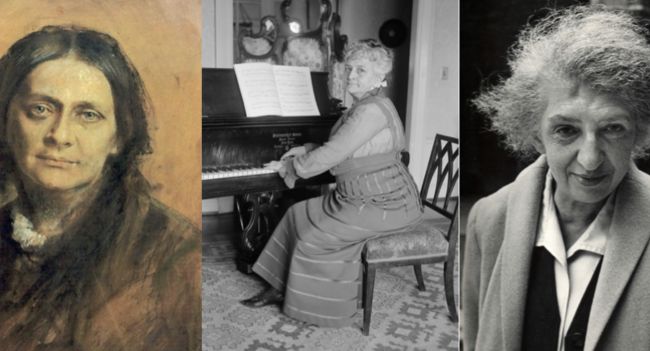

The Grand Matriarch

Born in Leipzig to a famed singer mother and a stern, demanding father, Clara Schumann (née Wieck) (1819–1896) seemed destined for musical greatness from an early age. Combining her own natural talents with an unrelenting regime of musical study set out by her father, Clara had already embarked on a life of performance before reaching double digits. At age 9, she met her famed future husband, Robert Schumann, at a performance in Leipzig, and he was so inspired by her playing that he decided to abandon his current studies in law to pursue music. Seeking to study with Clara’s own father, Robert moved into the Wieck residence, and, though nine years her senior, began to develop with Clara the relationship that would so powerfully define both of them in later years.

By age 18, Clara was already a piano superstar. In addition to regional critics and audiences, her brilliance at the piano was well noted by the musical giants on the day. Both Franz Schubert and Frédéric Chopin were impressed by her playing, as was the young Franz Liszt, who sang her praises in a published letter. In addition to her playing, Clara displayed a genuine talent for composition and would almost assuredly have gone on to become a leading composer of her day had the events of her later life not conspired to pull her away from the practice.

Despite their difference in age, Clara remained close with Robert Schumann throughout the decade since their first meeting, and when she turned 18, he proposed.

Innumerable speculations exist as to what effect their marriage and the role she played in it had on her musical potential, but it is generally accepted that, even though she would remain the most influential female figure in classical music throughout her own life and for decades to come after it, she was ultimately stifled by the demands of their union. While Robert Schumann would go down in history as one of the most prominent composers of his day, his tenuous mental health (which deteriorated dramatically later in life) would prove a constant preoccupation of Clara’s until his death in 1856. Clara’s role in their marriage while he was alive was largely one of house-keeper and mother to their eight children, but she also played a significant part in their financial well-being, performing concerts for money and managing their financial affairs. These duties, coupled in no small part with the historical bias against women in creative roles, prevented Clara from devoting herself to her craft as she might have otherwise.

And yet, despite all of this, she still managed to forge a rich musical life that was steeped in some of the most notable developments and personalities of the time. In addition to championing her husband’s works, she mingled with and performed the works of many of his contemporaries, including Chopin, Felix Mendelssohn, and Johannes Brahms. Brahms himself played a powerful role in her life, and proved a stalwart ally during the hard years of Robert Schumann’s mental illness. After Robert’s death, Clara was able to devote more of her time to touring and performing, which she often did with lifelong friend and violin virtuoso Joseph Joachim. In 1878, Clara accepted a post as a teacher of piano at Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt, and established a veritable lineage of piano pedagogy, gifting a new generation of piano greats with her depth of knowledge and skill.

In many ways, the life of Clara Schumann exemplifies the lives of many female musicians throughout the centuries. There is hardship and struggle, but also success and achievement. There is a constant battle against the demoralizing conventions of the status quo, coupled with the uncontainable will to express and produce great works of human creation. These are the antagonistic dichotomies women would face for many decades to come, and, even at this early stage, they already had a formidable role model to look back upon.

Beyond Clara Schumann, the mid and late 19th century witnessed the rise of what might be considered the first wave of widely recognized female piano greats. These women would set the bar for the next hundred years of classical piano practitioners, both male and female, and would leave a powerfully influential imprint on the history of classical music to come.

-Listen to Clara Schumann’s Piano Trio, Op. 17, here.

The First Wave: 1850 – 1900

The world of Western classical music was much smaller in the mid 19th century. Places that today are currently rich with the recognition and education of classical music (such as Asia) had not yet laid the groundwork for the development of aspiring virtuosos. As a young classical musician, if you wanted to learn from the best, you had to go to the source, and to be accepted at the source you almost certainly had to be a prodigal talent to begin with. It was hard to get closer to the source than to study with the likes of Clara Schumann and Franz Liszt, and from their pedagogical ranks emerged some of the great female players of the second half of the 19th century.

Among the students of Franz Liszt were several female players of note. Adele aus der Ohe (1861–1937) was one of the few child prodigies that Liszt accepted, and she started studying with him when she was 12. Another child prodigy to make Liszt’s shortlist was the Russian Vera Timanova (1855–1942), who was also recognized for her early talents by the eminent Anton Rubinstein, and later by Borodin and Tchaikovsky. Her legacy encountered a tragic end when, after performing her final concert at the remarkable age of 82 in 1937, she succumbed to hunger during the apocalyptic Siege of Leningrad in 1942.

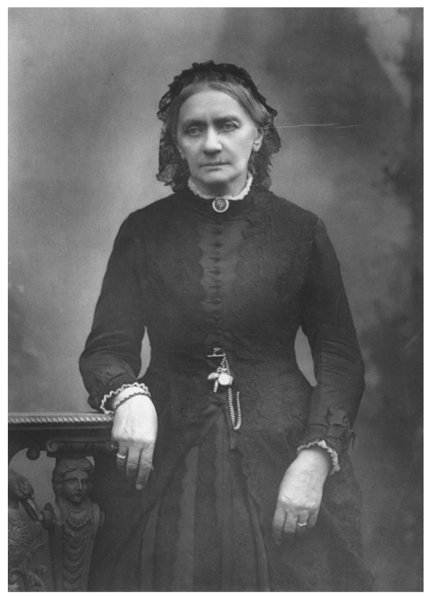

Liszt could even count a popularized namesake amongst his student roster; l’incarnation de Liszt, the tremendously well-regarded German virtuoso, Sophie Menter (1846–1918), was one of his favorite students, reportedly calling her his “only piano daughter.” Such was Menter’s skill and popularity that she was able to achieve an independence of repertoire and career few women of the day could manage. Case in point, one of Menter’s most popular and idiosyncratic performance pieces was a work known as Rhapsodies, which was in fact a compilation of several of Liszt’s own Hungarian Rhapsodies.

Clara Schumann could also boast a respectable list of vibrantly successful female proteges, including lifelong performer, composer, and fellow friend of Brahms, Adelina de Lara (1872–1961) and Fanny Davies (1861–1934) who, in addition to her respected prowess for Classical and Romantic composers, was an early proponent of the then-cutting edge music of Debussy and Scriabin. Davies also worked with Schumann’s favored violinist collaborator, Joseph Joachim, and would premier the works of a number of major composers, including Brahms and Edward Elgar.

Two of the period’s most well-regarded figures, however, came from different backgrounds entirely. English of blood, but French of spirit and residence, was the celebrated prodigy Arabella Goddard (1836–1922), who, as a child, played not only for the French Royalty, but for musical royalty in the form of Frédéric Chopin and George Sand. She gave the English premier of Beethoven’s ferocious “Hammerklavier” Sonata (Op. 106), and continued to perform Beethoven’s late sonatas for English audiences, who were entirely unfamiliar with them at the time. In the years between 1873 and 1876 she was involved in an international tour of Australia, India, and Asia, at a time when international tours were significantly more of a challenge to execute than they are today. Case in point, she spent a night of torrential rainfall in a small dinghy on the ocean when her ship wrecked between Java and Queensland, Australia. She would later become faculty at the Royal College of Music in London during its first year of operation in 1883.

From the other side of The Pond came another powerhouse of a player, the Venezuelan pianist, composer, conductor, and singer, Teresa Carreño (1853–1917). Called “the second Arabella Goddard” by famed Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw, Carreño was alternatively known as the “Valkyrie of the Piano” for much of her 54 year career. Carreño’s fame skyrocketed early, in no small part thanks to her parents emigration to New York City. There, she was heard and promoted by the popular virtuoso, Louis Moreau Gottschalk, and in 1963, at all of 10 years old, performed for Abraham Lincoln at the White House. From that point, Carreño’s career took her to Paris, where she mingled with the likes of Gioachino Rossini, Charles Gounod, and George Mathias. She later returned to the US to lead a busy performance life, and also exercised her talents as an operatic singer and composer. While she would spend a large part of the next thirty years touring and performing in the US, she did spend time in Europe, and accepted an invitation from the president of Venezuela to return there for several performances. The Teresa Carreño Cultural Complex in Caracas, which is the country’s most important performance structure, was named in her honor.

Carreño performed under the baton of many of the leading conductors of her day, including Gustav Mahler, Hans von Bülow, and Theodore Thomas. Her vast repertoire included everything from Beethoven and Schubert, Chopin and Liszt, to more contemporary composers like Edvard Grieg and Edward MacDowell. She is considered an early champion of the latter two composers. While no actual recordings exist of Carreño’s playing, she did record over forty works for the recording (or player) piano, which have been released in high quality production.

-Listen to Teresa Carreño’s reproduced piano roll recordings here.

Other notable women pianists who rose to prominence around the turn of the 19th century include close Ravel associate Marguerite Long (1874–1966), who, in addition to becoming a prominent professor at the Paris Conservatoire, joined forces with violinist Jacques Thibaud to create the Marguerite Long-Jacques Thibaud International Competition for violinists and pianists in 1943 (which is now known as the Long-Thibaud-Crespin Competition after internationally renowned soprano Régine Crespin), and also include the American sisters Rose and Ottilie Sutro (1870/1872–1957/1970), whose conjoined musical upbringing helped them to become one of the first officially recognized piano duo teams in history.

Before the War: Famed Teachers

The early decades of the 20th century witnessed a rise in the focus on institutional classical music training in the U.S., which opened up new opportunities for quality musicians to make both their names and their livings on the musically fertile American soil. While the perception and acceptance of women in classical music was noticeably changing, it was far from being a level playing field, and many women classical musicians were forced to contend with the real and imagined walls of social expectations, which, in general, frowned upon a woman’s pursuit of a lifelong career in touring and performance. While the most talented and well connected women could usually lay claim to such a career early in life, many found themselves more readily accepted as educators at high-profile institutes and in other functional but less glamorous roles.

Perhaps the most famous representative of this somewhat compromised category of female pianists is the stately and powerful pedagogue, Rosina Lhévinne (1880–1976), who, along with husband Josef Lhévinne, relocated from Europe to New York, and joined the faculty of the Musical Institute of Art (which would become the Juilliard School in 1926). The pedagogical prowess of the Lhévinnes was considered almost unparalleled in the U.S., and, in addition to the respect of his pianist luminary peers, Josef Lhévinne enjoyed a successful performance career. However, in order to allow Josef more unfettered access to the limelight, Rosina abandoned her own performance career when they were married, and would not reconsider re-entering the performance world until 50 years later, five years after Josef’s death in 1944. Having taught some of the leading pianists of all time, including Van Cliburn, Garrick Ohlsson, and John Browning, Rosina’s supporters were not about to allow her to so easily escape her own monumental performance potential, and in 1949 she reignited her performance career. Her concerts after this point were great critical successes, and her 1963 debut with Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic, at the not-so-tender age of 82, is generally regarded as her greatest moment as a soloist.

-Listen to Rosina Lhévinne play Chopin’s Concerto No. 1 in E-minor here.

Other female pianists to find something of a haven inside the doors of the Juilliard School included the Russian-born American, Ania Dorfmann (1899–1984), who was one of the few women to perform under the baton of the renowned conductor, Arturo Toscanini, and Olga Samaroff (1880–1948), who, in addition to being only the second pianist in history to have performed all of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas in public, was also the first woman to self-produce a concert at Carnegie Hall.

The War Years:

Few events of the 20th century altered the lives of so many people quite like the two World Wars, and the women of classical piano were no exception. For some, WWII and the events that surrounded it would prove a catalyst to their success and prestige, while others would emerge significantly more scarred by the horror and extremity of their experiences.

The role of morale keeper became an important one for many female pianists involved in the war effort. Beyond simply providing a moment of respite for beleaguered troops, the events and broadcasts provided by musicians of the time became something of a demonstration of solidarity and bravery at a time when the spotlight of recognition could be dangerously polarizing.

One of the most notable instances of such organized spirit-bolstering was a series of almost 2,000 daytime concerts organized by the formidable Dame Myra Hess (1890–1965) in the heart of London during the most dangerous years of WWII for the city, including the 1940–1941 London Blitz. A child prodigy herself, who attended the Royal Academy of Music and studied under Tobias Matthay, Hess brought together numerous pianists to play for these wartime concerts at a time when the concert halls of London were darkened at night so as not to attract the attention of German bombers. Hess herself performed in 150 of these concerts, and maintained her prominence after the war as a performer and educator.

-Watch Dame Myra Hess play her own arrangement of Bach’s chorale, “Wohl mir, daß ich Jesum habe (Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring) from Cantata 147 here.

Among the many remarkable musicians who joined the ranks for Hess’s London wartime concerts was another of the war period’s most popular female pianists Eileen Joyce (1908–1991). Compared by one critic to the likes of Clara Schumann, Teresa Carreño, and Sophie Menter, Joyce followed up a fascinating and adventurous road from prodigal, backwoods Australian talent to celebrated European debutant. Armed with a somewhat unconventional repertoire of Prokofiev, Liszt, and Shostakovich, Joyce forged herself into an instant hit, producing many recordings, giving concerts, and even landing spots in film. Unabashedly glamorous in her concert persona, Joyce was a known beauty, who would alter her dress colors based on the composer she was performing. While some of her fashion antics garnered her skeptics and doubters, her talents, and the extensive performance life and touring she produced by their merits, proved more than enough to render her a major player in history.

Other female pianists successfully able to navigate the challenges of the war to find success include the British socialite and expert Bach performer, Harriet Cohen (1895–1967), who, in addition to premiering a number of works written specifically for her by composers like Ralph Vaughan Williams, also took part in a 1934 concert that also featured Albert Einstein in an effort to help relocate scientists out of Germany, and notable Chopin interpreter Felicja Blumental (1908–1991), who escaped the increasingly anti-Semitic conditions in Europe with her husband in 1938, and relocated to Brazil, where she became a citizen and proceeded to promote and perform many of the works of the country’s composers. Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos wrote his Piano Concerto No. 5 in Blumental’s honor, and she was the one to premier it in London in 1955.

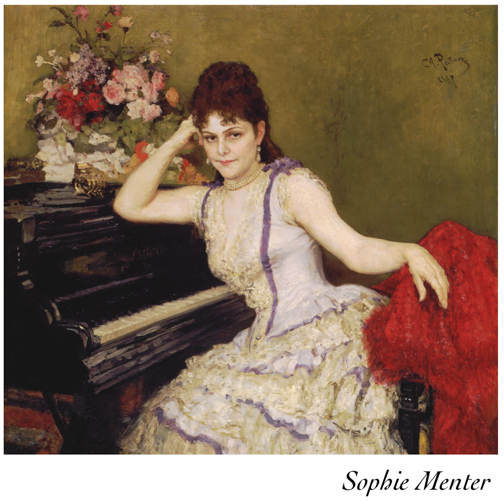

Australian pianist and educator Nancy Weir (1915–2008) landed a more hands on post during WWII. Another celebrated prodigy, she performed Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra at the age of 13, and made her way first to Germany, where she studied under Edwin Fischer and Arthur Schnabel, and then to London, where she studied under pianist and composer Harold Craxton. Already an excellent performer, Weir was also said to have an ear for technical musical depth and complexity comparable to Mozart.

The war cut what would prove to be an almost irredeemably large chunk out of Weir’s performance career, even though she would ultimately make use of her talents during the conflict as it progressed. At the commencement of the war, Weir joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, a wartime branch of the UK’s Royal Air Force. While her role originally seemed relatively innocuous (if somewhat secretive), it was later revealed that she was in fact using her prodigious ear for a much more dangerous task—listening in on German fighter pilot chatter and reporting the information back to her command. Word of her pianistic talents eventually got out, and she was relocated to the Middle East to entertain the troops, where she continued her spying. Among her final tasks during the war involved attending POW interrogations in Italy, where she claimed she had to parachute into Rome due to the destruction of the city’s airfield.

Weir’s post-war performance career was fairly minimal. By her own reckoning, when she returned from the war, the spark of the performance life had passed, and while she did go on to play a number of notable engagements upon returning to Australia in 1954, she mostly led a much more modest existence of regional performing and teaching. In addition to the sensitivity and clarity of her playing, she is often remembered for her coy and intelligent sense of humor, and for the many stories and legends that surrounded her concerning her musical skills and life experiences.

Another notable figure who rose to prominence in the early part of the 20th century was the masterful Bach interpreter, Wanda Landowska (1879–1959), who was known as a harpsichordist as much as she was a pianist. Obsessed with the harpsichord and with the music of the Baroque, she established something of a cultural haven for Baroque music and its performance at her home in Saint-Leu-la-Forêt in France before the war. Landowska and her student and lifetime partner, Denise Restout, fled from France to New York after the invasion of France by Germany, and later returned to find her home looted and most of her worldly possessions gone. Despite this, her career and musical standing were largely untarnished by the events of the war. She lays claim to the distinction of being the first keyboardist to record Bach’s Goldberg Variations on the harpsichord in 1933, and is also known for her often misquoted line, “You play Bach your way, and I’ll play Bach his way,” which is paraphrased from a quip to cellist Pablo Casals. The line is commonly thought to have been said to fellow harpsichord playing Bach specialist Rosalyn Tureck (1913–2003), who also ended up teaching at Juilliard, and who herself was very highly regarded by as a Bach player in general, and by a youthful Glenn Gould in particular.

-Listen to Wanda Landowska’s 1933 harpsichord recording of the Goldberg Variations here.

Not all female pianists emerged from WWII as unscathed as the women presented above. Those musicians unable to escape the European heartland before the Nazi’s consolidated their power found themselves living the lives of terror and survival that have become so infamously common in recollections of that period. It is difficult to ignore the fact that, in many cases of the survival of musicians during the war, it was their musical talents that saved them.

The career of Polish pianist Natalia Karp (1911–2007) was just beginning when the war broke out. After having made her debut with the Berlin Philharmonic at the age of 18, Karp moved back to Poland after the death of her mother, and married a lawyer who did not approve of her performance career prospects. Later, when her husband was killed in an 1943 air raid, Karp and her sister were captured and sent to the infamous Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp. There she encountered the camp’s brutally nefarious commandant, Amon Göth, who was known to torture and kill capriciously and mercilessly. Upon learning of Karp’s musical training, Göth ordered her to play him something on his birthday, and her rendition of Chopin’s Nocturne No. 20 in C-Sharp Minor so impressed him that he spared both her life and the life of her sister. Karp was eventually sent to Auschwitz, where she would almost certainly have passed under the ruthless gaze of the murderous Auschwitz lead physician, Josef Mengele, but managed to emerge intact from the horrors of the camp at the war’s end. She would go on to become a noted Chopin interpreter, making numerous tours of Germany, and even performing for Oskar Schindler, who was immortalized in Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List for the many lives he helped to save in the concentration camps, including Kraków-Płaszów. She would often perform with a pink handkerchief on the piano in memory of the war and its hardships.

Fellow Pole Maryla Jonas (1911–1959) also experienced the direct ramifications of contact with the Nazis. After showing early promise and studying with the famed Polish pianist and composer Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Jonas embarked upon a successful touring career of Europe, and would eventually go on to finish 13th in the 1932 International Chopin Piano Competition, and win the Beethoven prize of Vienna after that. In 1939, after the German invasion of Poland, Jonas was approached by the Nazi’s secret police, the Gestapo, and invited to Berlin to perform for Nazi officers in the city’s safer environs. Joans refused, and was subsequently arrested. She spent several weeks in Gestapo custody before a German officer who’d heard her perform before her arrest took pity on her and advised her to travel to the Brazilian embassy in Berlin. To get to the embassy, Jonas trekked the 325 miles between Warsaw and Berlin on foot, and with relatively little food and almost no shelter. Upon finally reaching the embassy, Jonas was provided with false papers, and sent on her way to make the additionally lengthy trip between Berlin and Rio de Janeiro. Unfortunately, while the physical danger might have been over, the psychological damage proved lasting, and, after experiencing a nervous breakdown, Jonas was committed to a mental hospital for several months in 1940. Further poor news concerning the deaths of relatives would delay her recovery further, but with the support of her sister and fellow Polish piano master Arthur Rubinstein, Jonas was able to resume her performing in South America, and eventually made her debut at Carnegie Hall in 1946.

Other notable female pianists from the war period include Vera Bradford (1904–2004), who was known for the incredible power and control she brought to her interpretations of Brahms, Rachmaninoff, and Liszt, Dame Moura Lympany (1916–2005) who was among the first musicians to play in Paris after the Liberation in 1945, and Gina Bachauer (1913–1976), who also played for Allied troops in the Middle East, and in honor of whom the Gina Bachauer International Piano Competition was established in 1976.

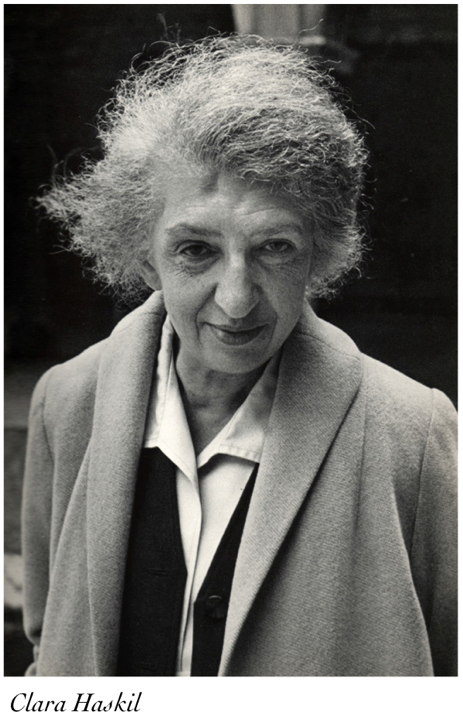

Finally, we would be remiss to leave this period in history without mentioning a pianist who struggled with and ultimately overcame her own demons to become one of the highest regarded Mozart interpreters of her day, the Romanian pianist Clara Haskil (1895–1960). Haskil’s talent as a child was so pronounced that she was accepted into the Bucharest Conservatory at just 6 years of age. She then went on to study with esteemed professor Richard Robert in Vienna, and finally to the Paris Conservatoire to the class of the legendary pedagogue Alfred Cortot. After graduating, she commenced a series of small but successful tours in Europe and the US.

Haskil’s luck started to turn at the age of 18, when the onset of a debilitating scoliosis forced her to accept a body cast, and her general health experienced a sharp and trying decline. While she would still give some performances after having the cast removed, she began suffering from a powerful stage fright in 1920, and the combination between that and her delicate health would scuttle her performance career for nearly thirty years. As a result of this, Haskil lived largely impoverished for most of her life, and was forced to navigate the tumultuous years of the war in Europe with few resources and little personal support.

Things shifted back in the positive direction in 1949, when Haskil was able to overcome her fear and health issues to return triumphantly to the performance scene, starting with a series of concerts in Holland. Over the next ten years she would play under the batons of numerous conductors, and would collaborate with some of the greatest instrumentalists of her day, including Pablo Casals, George Enescu, and Issac Stern. Her last year of life was also arguably her most successful, and her November 1960 recording of Mozart’s Piano Concertos No. 20 in D-minor and No. 24 in C-Minor with Igor Markevitch and the Orchestre des Concerts Lamoureux is still regarded as a seminal recording of these works.

-Listen to Clara Haskil’s 1960 recording of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 20 in D-minor here.

After the War: The Middle 20th Century

The world of female classical pianists experienced a proliferation of notable and important figures in the decades after WWII. More and more, the women of classical piano were hailing from less traditional musical and ethnic backgrounds, exploring new and adventurous repertoire, and reaching new heights of professional and artistic excellence. While the challenges facing female classical musicians relative to their male peers were still far from leveled, it was steadily becoming more common for female talents to receive the early support they needed to progress into the professional performance world. In this final section of our article, we will look at some of the more modern female masters whose influence has been felt throughout the classical piano world.

There are some composers who are simply considered essential for every classical pianist to have studied and performed. Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann, Chopin, Brahms, Liszt, Debussy, Rachmaninoff…a lineup similar to the one we opened this article with, all of which typically fall under the “required reading” category of piano performance. Obviously, the piano world consists of much more than the everlasting works of these and other, similarly great composers, however many classical pianists make their entire careers out of repeating brilliant, but, well, repetitious renditions of these works. This is not unreasonable, as much of the broader classical music audience, even to this day, favors this all too familiar canon of sonatas, concertos, nocturnes, preludes, and etudes, to an almost obsessive degree. As easy as it is to become a drop in the sea amongst the many, many pianists who pursue their careers by riding the backs of these mighty musical creators, it takes even more courage and finesse to create a successful career through a repertoire that does not feature them.

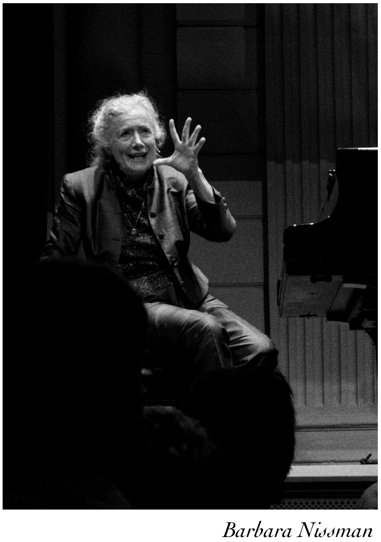

Several female pianists in the post-WWII classical piano world became some of the earliest and most successful representatives of this “alternative repertoire” bravery. Alicia de Larrocha (1923–2009), often remembered as perhaps the greatest Spanish pianist in history, made extensive recordings of Spanish composers such as Isaac Albéniz, Manuel de Falla, Enrique Granados, Fredrico Mompou, and Antonio Soler, in addition to more standard repertoire from Beethoven and Liszt. American pianist Ruth Laredo (1937–2005) championed the challenging and mystic works of Scriabin, and became the first pianist to record all of his sonatas. The more contemporary pianist Barbara Nissman (b. 1944), has established herself as a pinnacle of musical expertise surrounding the works of Sergei Prokofiev and Argentinian composer Alberto Ginstera, who dedicated his Piano Sonata No. 3 to her, and which she premiered in 1982. Nissman is also famed for being the first pianist to tackle all of the Prokofiev sonatas in a performance series, which she gave in New York and London in 1989.

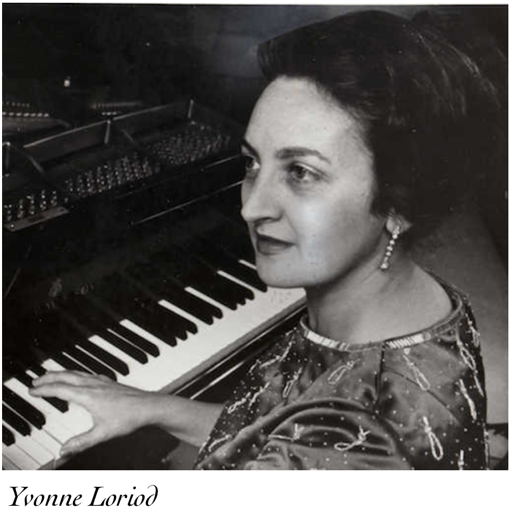

In terms of composer speciality, however, few can compare to the dedication given by pianist Yvonne Loriod (1924–2010) to the demanding and often abstract works of Olivier Messiaen. Not only was Loriod to give most of the major premieres of Messiaen’s work, she was often an inspiration behind many of his technical choices in constructing his piano works. That Loriod would go on to become Messiaen’s second wife would seem not inconsequential to the success of this relationship, however, it should be noted that Loriod was a student of Messiaen’s well before their marriage would take place. Of Loriod’s prowess at the keyboard, Messiaen claimed that he felt he had the ultimate in freedom of writing, knowing as he did that Loriod would master any challenge he sent her way.

-Listen to Yvonne Loriod playing Messiaen here.

This is not to say that excellence in the more traditionally accepted repertoire has not been a source of great success and recognition for the female pianists of the latter part of the 20th century. Pianists such as Rhondda Gillespie (1941–2010), whose specialization was in Liszt, and Halina Czerny-Stefańska (1922–2001), whose repertoire consisted almost entirely of Chopin, very clearly carved a name for themselves in the annals of pianistic excellence. The latter was proven to be the real pianist behind a 1966 release of a recording of Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-Minor, which was originally attributed to famed Romanian pianist Dinu Lipatti. Beloved teacher, mentor, and Vladimir Horowitz confidant Constance Keene (1921 – 2005) was noted, among other things, for her landmark 1964 recording of Rachmaninoff’s Preludes. Meanwhile, the introverted and introspective Chinese pianist Zhu Xiao-Mei (b. 1949) came up as a respected Classical performer, but has since evolved into one of the modern day’s foremost Bach interpreters, and was invited to perform at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, where Bach worked for over twenty years, and where his grave is located.

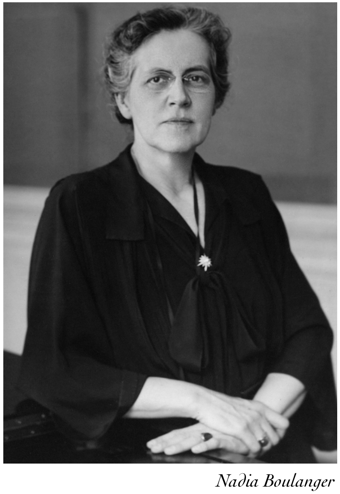

It is appropriate here to mention a figure known far more as a composer than a pianist, whose influence was nonetheless felt throughout many musical realms, not least of which was that of classical piano. The French composer and estimable pedagogue Nadia Boulanger (1887–1979) taught many of the world’s foremost composers and musicians, and has left us with an indelible print of both her talents as a teacher and as a composer. In addition to teaching numerous composers who went on to great success, Boulanger had a lasting influence on many of the pianists who came under her tutelage. Among her most notable female pianist students are the recording powerhouse, professor, and record label director Carol Rosenberger (b. 1933) and the Turkish Romantic specialist, idil Beret (b. 1941).

While there are many fantastic female pianists to speak of in terms of sheer skill and power to fill out the decades in the back half of the 20th century, we will mention two here of special note.

Dame Mitsuko Uchida (b. 1948), born in Japan but naturalized in Britain, Uchida studied in Vienna with noted masters such as Wilhelm Kempff and Stefan Askenase. After winning a number of prestigious awards in her twenties, Uchida went on to make her name as an acclaimed interpreter of Classical and Romantic literature. Winning several Gramophone Awards through such recordings as her 1989 complete Mozart sonatas compilation, some of Uchida’s most notable achievements revolve around her expertise and love of the composers of the Second Viennese School, the most prevalent of which for the piano are best represented by Arnold Schoenberg and Anton Webern. Her 2001 recording of Schoenberg’s Piano Concerto with Pierre Boulez won her another Gramophone, and is considered a seminal recording of the work. Uchida is also a notable conductor, advocate, and executive member for a number of high profile musical entities and foundations.

-Watch Mitsuko Uchida play Schoenberg’s Piano Concerto here.

With so many remarkable pianists to choose from, naming the “greatest” of all is something of a fool’s errand. However, in terms of living female pianists, few names are mentioned with the same reverence as that of the extraordinary Argentinian master, Martha Argerich (b. 1941). Born in Buenos Aires, Argerich first put her fingers on the piano at age three, began serious lessons at 5, and gave her first full concert at age 8. Upon moving with her family to Europe in 1955, Argerich studied primarily under pianist and composer Frederich Gulda, and sought out lessons when she could from other piano experts, including four essential lessons she managed with the brilliant Italian virtuoso Arturo Benedetti Michaelangeli. After winning first in the seventh International Chopin Piano Competition at age 24, the multi-faceted and multi-lingual Argerich commenced what to this day has been a breathtaking career as a performer and recording artist, working largely with collaborators and orchestras since the early 1980’s. Many of her recordings of the great composers are considered essential interpretations. Her recordings of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 are nothing short of astonishing. Averse to the attention of the media, Argerich may not be the most visible pianist in history, but she is undoubtedly among the most important.

-Watch Martha Argerich perform Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto here.

Trailblazers, and Into the Future

The classical piano world of the past fifty years has been filled with a wealth of fantastic female players and trailblazers. Pianists like Ludmila Valentinovna Berlinskaya (b. 1960), Olga Kern (b. 1975), and Joanna MacGregor (b. 1959) have come to represent not only the continuing high-standard of musical excellence, but also the increased ability of modern female pianists to hold powerful roles in esteemed musical organizations and institutions.

Meanwhile, the evolution of technology has afforded female classical pianists access to markets and opportunities beyond the confines and constructs of traditional venues and media. Such avenues have also allowed women to show off their determination and ingenuity. For example, American pianist Simone Dinnerstein (b. 1972) launched her career by releasing a self-financed recording of the Goldberg Variations in 2007. The album outsold the White Stripes on Amazon, and reached No. 1 on the Billboard classical music album sales chart. Since that success, Dinnerstein has embarked upon a rich career of performance, collaboration, and recording, all made possible by her leap of faith (and financial risk-taking). Ukrainian-Amercian pianist Valentina Lisitsa (b. 1973), was one of the first classical pianists to take her career digital by posting videos of her playing on YouTube. She has since garnered well over 50 million views.

Finally, women pianists have also been a the forefront of evocative new takes on what is considered acceptable performance practice in classical music. Venezuelan pianist Gabriela Montero (b. 1970) has the familiar history and trajectory of a classic prodigy, but has assumed a unique identity and speciality in her mature career. Having been gifted with a toy piano in her crib as a baby, Montero could be said to have started her relationship with the piano as early as seven months of age. She gave her first public performance at age 5, her concerto debut at 8, and went on to study at the Royal Academy of Music in her early twenties. By Montero’s account, she was one day doing some improvising at the piano when she was overheard by classical piano legend Martha Argerich, who was so impressed that she encouraged the Montero to incorporate her improvising into her performances. While improvisation was at one time a valued aspect of performance in the classical world, it fell out of vogue in the later decades of the 19th century, and has not gained traction since. While not entirely unheard of in the modern day, improvising classical-style piano has yet to reach a general practice within the greater classical world, and musicians include it into their performance programs at their own risk. That risk has payed off splendidly for Gabriela Montero, who’s adept and seamless improvisations, whether free-form or on a specific theme called out by an audience member during one of her performances, stand beside more traditional repertoire like impromptu compositions all their own.

-Watch Gabriela Montero speak and improvise on a very special theme here.

Conclusion: New Horizons

The future is bright for the women of classical piano. In addition to the rich history of fellow female players to look back upon for inspiration, modern young women of the piano are having to contend with far fewer of the social hurdles faced by their predecessors. If we’re not there already, we’re certainly close to being at a point whereby the distinction between male and female is inconsequential when considering the artistic and professional potential of an individual. And with young luminaries like Yuja Wang (b. 1987), Anna Fedorova (b. 1990), and Anastasia Rizikov (b. 1998) providing a high-profile picture for a new generation of female talents to aspire to, its safe to say that we can only look forward to wonderful things from the future women of classical piano.

We hope that you have enjoyed this article, and that you will continue to keep your eyes and ears on the endeavors of women classical pianists the world over!