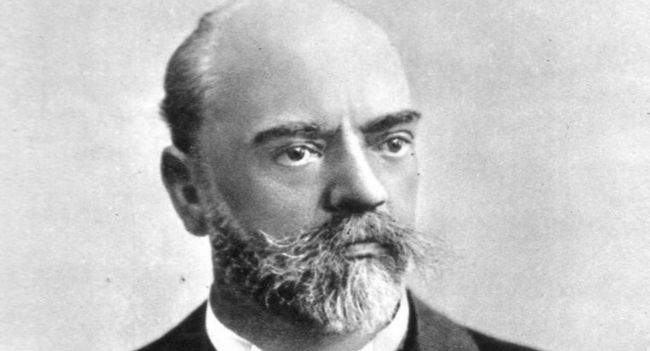

Read on for our guide to the life and music of the Czech composer Antonín Dvořák, creator of some of the most masterful and melodramatic music of the late 19th century.

Who was Dvořák?

Antonín Dvořák is one of the most important composers of the 19th century, and also one of the easiest to love.

Why is Dvořák a great composer?

His importance lies partly in the way he synthesised the folk music of his native Bohemia and neighbouring Moravia (now the Czech Republic) with classical music, arriving at a very successful late Romantic style with vivid folk inflections and rhythms.

In this way, Dvořák belongs at the centre of that flowering of 19th-century classical music with strongly national roots, just as, for example, Sibelius’ music draws on the myths and legends of his native Finland, or the music of Musorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Balakirev, and others has a pungently Russian soundworld, operating at a distance from the separate Western classical tradition.

But another huge part of the draw of Dvořák is the sheer melodic joy of his writing, whether for full orchestra, string quartet, solo voice, or many other combinations. Listen to, for example, the first five minutes of Dvořák’s Eighth Symphony, and you hear a composer simply bursting with melodic and rhythmic ideas.

The classical tradition is heard in a rich and vital form; the birdsong of Dvořák’s beloved Bohemian woods and fields is evoked; and the result is one of the most exciting and atmospheric few minutes in the whole of classical music. Dvořák’s closest musical contemporaries were Brahms and Tchaikovsky, and music like this stands shoulder to shoulder with the great works of those two.

What nationality was Dvořák?

Dvořák was born in Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic but at the time a part of the Austrian Empire.

When was Antonín Dvořák born?

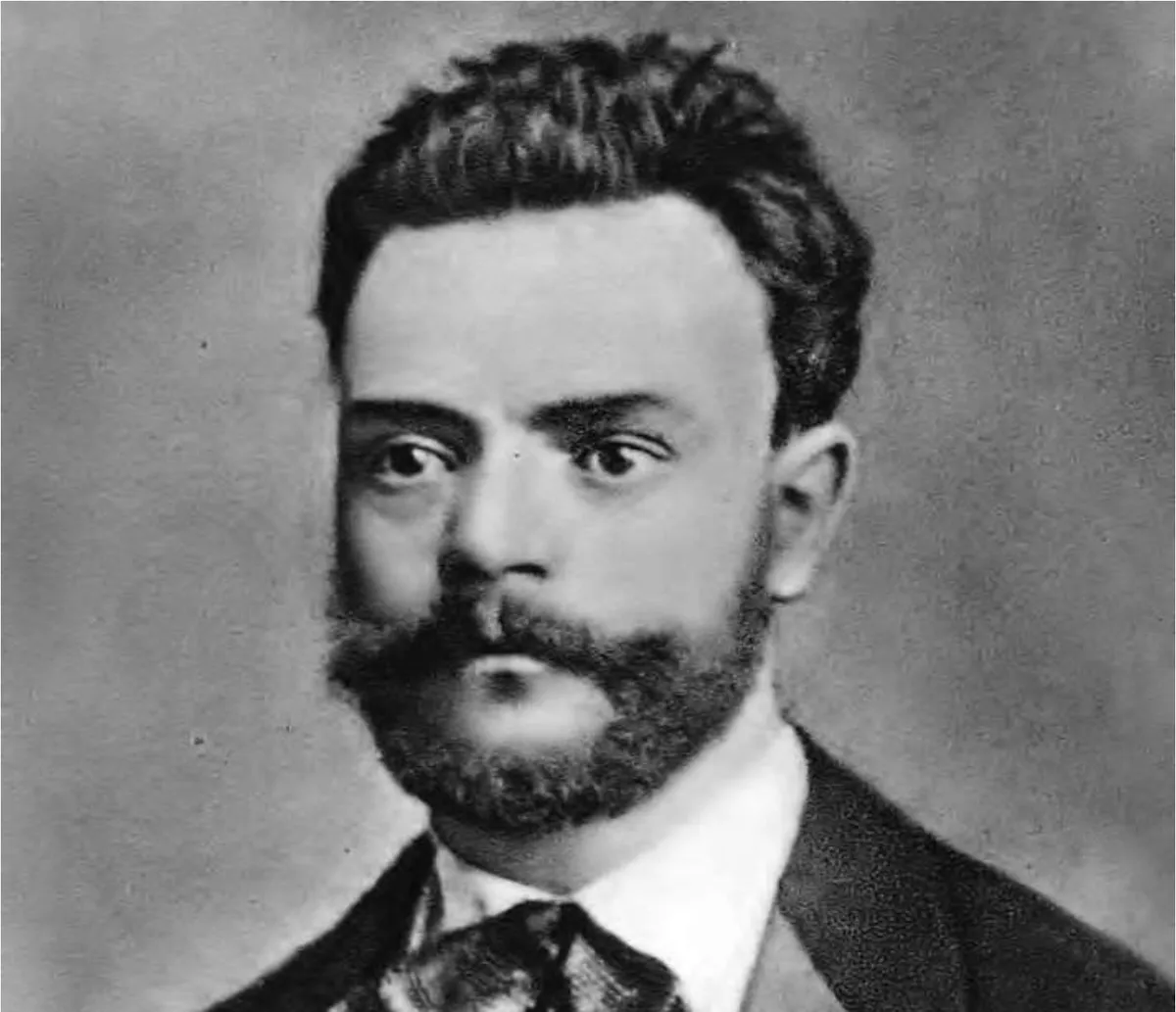

The composer was born on September 8, 1841, in the town of Nehalozeves near Prague.

Where did Dvořák grow up?

He grew up first in Nehalozeves, though he later moved, at age 13, to the town of Zlonice. There, he lived with his uncle and learned German.

His German teacher, Antonín Liehmann, also gave the young Antonín organ, piano, and violin lessons, as well as lessons in music theory. Liehmann was also Zlonice’s church organist, which meant that Antonín was sometimes asked to play the organ at services.

What instrument did Dvořák play?

The young Antonín took up the violin at age six or seven. He showed great skill, too, playing in a village band and in church.

Where did Dvořák study music?

After Zlonice, Dvořák went to Prague to study at the city’s Organ School in 1857. He graduated two years later, finishing second in his class.

Dvořák’s early composing career

Despite the conventional aspects of his musical background and education, Dvořák’s early compositions were marked by a strong experimental tendency.

None but his closest friends were aware that he was composing during the 1860s. His income derived mainly from playing viola in the Prague Provisional Theatre Orchestra and giving music lessons. But this did not prevent him from writing two symphonies, a cello concerto (not the famous one, but a lyrical work in A major), and a flurry of chamber works.

Dvořák’s Cypresses

The key composition from this time, however, is the song cycle Cypresses. These 18 songs are remarkable, with the fifth song looking far beyond the Prague of the 1860s to a melodic and harmonic language more familiar from Janáček and Debussy.

The climax of this experimental phase came with the E Minor String Quartet, No. 4 (c. 1868–1869), a work of amazing originality that marks the young composer as a musical revolutionary. Cast in a single 40-minute span, Dvořák pushed romantic tonality to its limits, some 30 years before Schoenberg outraged the grey-beards of Vienna with Verklärte Nacht.

In the early 1870s, Dvořák’s more extreme empirical tendencies began to wane, but not before he had exercised them (in 1871) in the splendidly rich first version of The King and the Charcoal Burner and the majestic sweep of the Third Symphony in E flat major (1873).

Who influenced Dvořák?

But through the 1870s, thoughts of studying with Liszt gave way to a more classical approach to form and the more moderate influence of Brahms. Dvořák had also settled down to family life, marrying Anna Čermáková in November 1873.

His music from the mid-1870s is also touched by a more obvious national accent. The melodies in the pastoral Fifth Symphony of 1875 have a freshness and symmetry that show this new influence. The works that clinched this tendency and also guaranteed the growth of his European reputation were the first set of Slavonic Dances of 1878.

For home consumption in the 1880s, Dvořák wrote Dimitrij (1882) and The Jacobin (1888). Foreign commissions resulted in what is usually thought of as his finest symphony, the Seventh, and a handful of choral works.

Alongside this, Dvořák found the time to write a series of chamber works, including the popular A major piano quintet, Op. 81, another set of Slavonic dances, songs, and piano music. Had it not been for his trip to America, his string of popular works, to which the Eighth Symphony was added in 1889, would have maintained his place in everyone’s affections. But more popularity was to come.

Why did Dvořák go to America?

Dvořák went to New York in September 1892 in order to become director of the National Conservatory of Music. While much of his time was taken up with teaching, he also found time to compose. The allure of the New World Symphony is not hard to fathom; the clarity of the outline and a string of hummably memorable themes have commended the work to audiences from the premiere to the present day.

There is a new pungency and vitality to this and the other great ‘New World’ works: the American Quartet, the E flat String Quintet, the great Cello Concerto, and the Biblical Songs. The only cause for regret is that these works have somewhat overshadowed so much else in his output, not least the operas and the rewards and challenges of his early music.

A global success

Ever since audiences in Britain and Germany discovered Dvořák in the early 1880s, he has played an important part on the world’s musical stage. But in our own century, his reputation has tended to rest on a relatively small part of his output. In many ways, 19th-century audiences in Britain knew a broader range of Dvořák’s work than we do today. The great choral compositions—the Stabat Mater, The Spectre’s Bride, St. Ludmila, and the Requiem—were performed and appreciated widely.

Why did Dvořák’s reputation suffer under Communism?

Yet perhaps most curiously is the way in which, after his death in 1904, this most famous of Czechs suffered a downturn in reputation in his native land. Led by an unsavoury demagogue called Zdeněk Nejedlý, a squad of critics set out to undermine Dvořák’s achievement, claiming his work was not truly Czech and lacked the virtue of reflection, qualities they found in Smetana.

Nejedlý pursued his campaign with all the advantages of high office in the Communist government from 1948; only since the Velvet Revolution have the Czechs more thoroughly re-examined the status of their greatest composers.

The operatic Dvořák

In his later years, Dvořák thought of himself primarily as an opera composer, and this image deserves consideration. Until the 1950s, English translations of Czech operas were rare. Smetana’s The Bartered Bride acted as a trailblazer, followed by a Janáček revival.

Now it’s surely Dvořák’s turn: while his early works suffer from poor libretti, The Devil and Kate, The Peasant and the Rogue, Rusalka, Dimitrij, and The Jacobin, once staged, rarely take off. The exquisite fairy-tale opera, Rusalka, became something of a favourite in David Pountney’s beautifully eerie production at the London Coliseum in the Eighties and more recently asserted its popularity at Glyndebourne.

Is Dvořák underrated?

One reason Dvořák has been neglected may be due to a lack of sensationalism in his life: his steady career and happy marriage were unlikely to project him into the big league inhabited by the monsters and the nervous wrecks of Romantic art.

His early musical education in the schoolrooms and organ lofts of Nelahozeves, the hamlet near Prague where he was born, and Zlonice and Kamenice, where he later studied, probably differed little from that of his distinguished eighteenth-century predecessors. The solid virtues of figured bass and a rigorous approach to harmony and counterpoint—reinforced by two years at the Prague Organ School—provided Dvořák with a firm foundation for a lifetime of composition.

Composers like Dvořák

If you like Dvořák’s music, the symphonies and chamber music of Brahms and Tchaikovsky are likely to appeal. If the lively Czech rhythms in Dvořák’s music capture your attention, try other great Czech composers such as Smetana, Janáček, and, especially, Martinů.