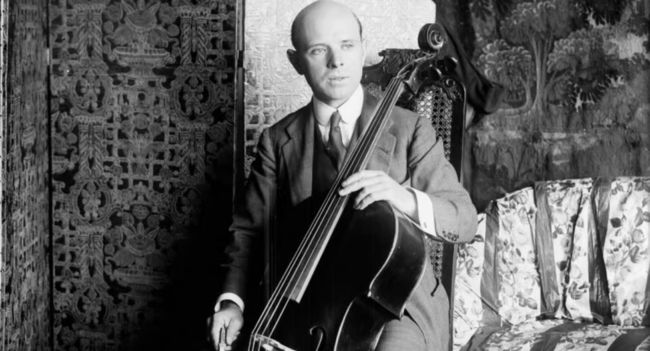

Pablo Casals was a towering figure in the history of cello playing—at once artist, exponent, exemplar, and liberator. The greatest among his musician colleagues revered him: Fritz Kreisler called Casals “the greatest musician ever to draw bow”; Joseph Szigeti spoke of “the witchery of what is probably the greatest art among all string players”; and conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler declared, “those who have never heard Pablo Casals have no idea how a string instrument can sound.”

Another admirer was David Oistrakh, who enthused, “Perfect intonation, free movement of the hand along the fingerboard, the greatest refinement and polish of any bowings—that is a real miracle. I have never before seen anything like it.”

Born into an epoch when cellists still labored under old-fashioned technical strictures, including the holding of the bow-arm very close to the body, Casals found a new way to play. His style of bowing may not have pleased his teachers, but it provided future players a model of physical freedom, while demonstrating that the cello could be as expressive as any instrument. His approach to vibrato was equally new: He vibrated liberally and at times continuously, paralleling the innovations of his violinist contemporaries Kreisler and Jacques Thibaud.

Casals brought Bach’s previously neglected Suites to the light of day, revealing them as the musical masterpieces that they are. And he lived a life of moral courage, leaving the public stage out of political principle, before returning to play and conduct into his tenth decade. For novelist Thomas Mann, he was “one of those artists who come to rescue humanity’s honor.”

Casals was born in 1876 in the Cataluñan town of Vendrell. His father, a carpenter and church musician, taught him to play piano and organ and to sing. When young Pau was 9, a troupe of clowns came to town. One of them played on a strung-up broom handle, and Pau became obsessed with the instrument—so his father built him his own first stringed instrument out of a gourd. At 12, the boy finally heard a real cello, and soon after embarked on cello studies in Barcelona, where, in a bookstore, he came across a copy of Bach’s Suites. He would work on them for twelve years before venturing to perform them in public.

At age 13 Casals was already playing in a piano trio at a Barcelona cafè. Two years later he was heard there by the composer Isaac Albéniz, who helped introduce him into Madrid society. Young Casals promptly became a favorite of Queen Maria Cristina. In 1899 he made a London debut, and in 1901 he played in Paris, soon settling there. For the next three decades, he enjoyed a brilliant career as soloist, conductor, and member of a superstar piano trio with his friends Thibaud and Alfred Cortot.

Casals became known for the force of his musical personality, for his extraordinary and expressive intonation, and for that unprecedented freedom of bowing. He also became known for the grunts and moans he liberally emitted as a result of his total immersion in the music.

Casals’ life changed in 1936 when the Spanish Civil War broke out. He withdrew almost completely from public performance, particularly boycotting countries that recognized the victorious Franco government. He played his last professional concert in the United States in the 1920s (though he would return to play at the Kennedy White House in 1963). With the advent of WWII, Casals broke off relations with fellow artists such as Thibaud and Cortot, whom he viewed as too accommodating toward Fascist regimes. Retiring to southern France, this musical giant faded from public view.

But then, in 1950, Sascha Schneider organized the first Casals Festival in Prades, France. It became an annual event. Casals himself founded a second festival in Puerto Rico in 1956, and from this time until his death in 1976 he was once again a titanic presence in the music world. At the age of 95, he was awarded the United Nations Peace Medal.

Casals’ recorded output is perhaps not what one would wish for from such a giant. His reclusion from public life included a hiatus from recording. And when he did return to recording in older age, his playing had become, in the words of his student Bernard Greenhouse, “more exaggerated and less accurate.”

Nonetheless, there is a wealth of great Casals recordings—beginning with his Bach Suites, recorded in the 1930s. Casals identified himself closely with Bach, immersed himself in the Suites, and took a profoundly spontaneous attitude to interpreting them. Greenhouse describes the approach: “You must learn it so well that you remember every single idea that you have had in your practice. Then you forget everything and improvise.”

Mstislav Rostropovich felt that “when Casals played it seemed to me impossible to interpret Bach in any other way, such was the force of his personality and his nature as an artist, his total conviction in what he was doing.”

Casals’ magnificent 1920s trio recordings with Thibaud and Cortot are impossible to choose amongst: Beethoven’s “Archduke,” Schubert’s B-flat D.898, Mendelssohn’s D minor, and Schumann’s D minor are all given timeless performances. A later great chamber music recording is the Schubert Cello Quintet with partners Isaac Stern, Schneider, Milton Katims, and Paul Tortelier, from the 1956 Casals Festival.

In 1937, in a rare wartime appearance, Casals performed and recorded the Dvorák Concerto with Szell and the Czech Philharmonic; a contemporaneous review aptly describes it as “seemingly played with a sword rather than a bow.” Casals also recorded the Beethoven sonatas in the ‘30s, the third with Otto Schulhoff, and the others with Mieczyslaw Horszowski; the performances are brilliant, creative, and gorgeous.

Casals’ Elgar Concerto was considered by some audiences to be un-English in its frank emotionalism, but the dignity and pathos of his 1945 recording with Boult and the BBC Symphony are unlikely to attract many detractors today.

During the first decades of the century, Casals made a plethora of encore recordings, displaying a variety of wonderful qualities. Greenhouse felt that, in Casals’ Chopin recordings, “you hear musicality that is unsurpassed. Nobody could ever match his level of artistry.” Examples include the E-flat Nocturne and the “Raindrop” Prelude.

In the central section of the Granados Andaluza, Casals finds a uniquely communicative, conversational tone. His Saint-Saëns “Swan” is eloquent, and his Godard Berceuse lovingly expressive. Schubert’s Moment Musical, Popper’s Mazurka, and Sgambati’s Serenata Napoletana all boast a rare rhythmic stylishness. Finally, in a late recording of Falla’s “Nana,” Casals bares his soul.