Quaker missionaries lured the little Sioux girl with tales of orchards. Come with us, they said, and we’ll bring you to school.

Her widowed mother protested. She’d lost a son to white missionaries before. But her little girl begged and begged, eager to escape to a faraway place where she might pursue knowledge and eat red apples.

Finally her mother relented. The seven-year-old boarded a train and journeyed seven hundred miles. When she arrived at the school, it was February. The air was cold and the branches of the apple trees were bare. She immediately burst into tears.

The school was White’s Manual Labor Institute in Wabash, Indiana, and the little girl’s experiences there read like the early chapters of an American Jane Eyre. Teachers beat students. Young friends died from neglect and malnutrition. Students were forced to rise early in the day to study and do hard labor. The girl’s long black braids were forcibly cut. White’s Institute was part of an entire culture that sought to suffocate her very identity.

But she emerged clutching that identity more tightly than ever.

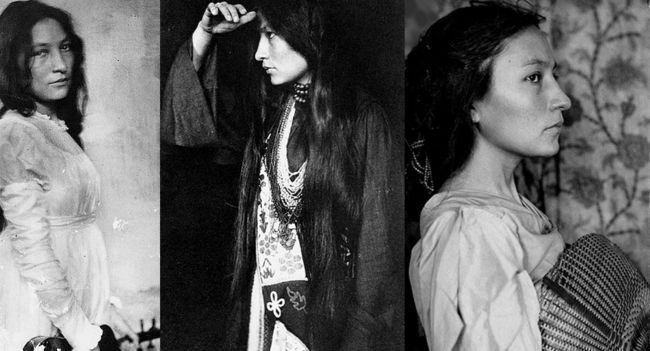

Gertrude Simmons, later known as Zitkála-Šá (“Red Bird”) is best known today for her activism and writing. And for good reason, too: the brutal, poetic honesty of her essays can take your breath away. But Zitkála-Šá was also renowned for her mastery of the violin, the piano, and the voice. Western art music was a tool that she used to cope with abuse, garner praise and respect, and shatter stereotypes of Native people.

In 1913 she collaborated on a groundbreaking work, The Sun Dance Opera. It is the first opera written by a Native American, and it employed elements of Native folk music. Unsurprisingly, her white male collaborator took more credit than he was likely due. He copyrighted the score under his name alone, despite citing Zitkála-Šá as a creative partner in his memoir. We don’t have any first-person account of its composition from Zitkála-Šá, and so we are forced to squint between the lines and fill in the blanks ourselves.

Doing so is worthwhile. For those interested in Western art music, the story of Zitkála-Šá is uniquely challenging and rewarding. It raises a variety of questions we still struggle with today. Is Western art music really a universal language? Might it bridge cultural chasms, or does it cause them? How might it oppress, and might it give the voiceless a voice?

Zitkála-Šá was born Gertrude Simmons in late February 1876 in Yankton, South Dakota, near the Nebraska border. She was the product of a short-lived marriage between an abusive Frenchman and a widow named Tate I Yohin Win (Reaches for the Wind, or Every Wind), also known as Ellen Simmons. Tribal elders compensated for the lack of a father figure, and she remembered her childhood as idyllic. But her innocence was shattered in 1884 when she arrived at White’s Institute.

She spent three years there. At eleven she returned to Yankton, then at thirteen she briefly attended the Santee Normal Training School in Nebraska. This geographically and culturally disjointed upbringing put great strain on her and her mother’s relationship. In 1890 Gertrude opted for the once unthinkable: to return to White’s Institute. She departed in December, the same month as the Wounded Knee massacre, which occurred a few counties to the west.

At White’s Institute, Gertrude threw herself into her studies, proving exceptionally gifted at the violin and piano, as well as recitation and oration. In June 1895 she delivered a rousing commencement speech entitled “The Progress of Women”, which asserted that “half of humanity cannot rise while the other half is in subjugation.” The local paper raved.

She opted to attend Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, where she was the only Native in the student body. She took a variety of classes, joined a music club, and sang and performed in public. Much to the dismay of the senior class, as a freshman, she won a college-wide oratory contest.

The win made her eligible to attend a statewide competition held at the Indianapolis Opera House. She ascended to the stage only to see a racist banner unfurled across the balcony. Nonetheless, her speech on the necessity of Native equality won second place. (She would have placed first, but one judge was Southern and furious over her disparagement of slavery.)

The stress and excitement soon caught up with her, and her health began deteriorating. Exhaustion combined with financial concerns led her to drop out of Earlham after three trimesters.

In 1897, Gertrude found a job teaching at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School (CIIS) in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, the best-known boarding school for Native Americans in the country. Like White’s, this school was designed to stamp out students’ cultural identities. Here she sang at school events and conducted the Minnehaha Glee Club. She was even selected as violin soloist for the CIIS Band’s upcoming tour. That summer she began focusing on her violin playing in earnest, studying with a Leipzig Conservatory graduate named Professor Taube. She also traveled to New York and met with Gertrude Käsebier, the best-known female photographer in America. Käsebier apparently encouraged Gertrude to pursue her many talents as far as they would lead her. This encouragement provided serious food for thought.

Thanks to a grant from the commissioner of Indian Affairs, she began studying music in Boston with Eugene Gruenberg, an early Boston Symphony member. She considered attending the New England Conservatory of Music, but her relatively advanced age – 23 – put her at a marked disadvantage to players who had started earlier.

So she shifted her creative energy to writing. Over the following months she produced a series of essays for Atlantic Monthly, which appeared in the first three months of 1900. They were autobiographical in nature and critical of the brutal education that many Natives had endured. To underline her embrace of the Native portion of her identity, she signed these stories Zitkála-Šá (Red Bird).

Zitkála-Šá returned to the CIIS in early March 1900 and began rehearsing for the tour. A recitation – “The Famine” from Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha – was added to the program. Zitkála-Šá also opted to appear wearing traditional Native dress. These performances were unmitigated successes. “She held every ear and the recourse frequently to handkerchiefs told how great an effect she was exerting over her audience,” reported the Trenton Daily Gazette. She not only performed for Longfellow’s daughter, but the McKinleys at the White House itself.

However, in the eyes of the CIIS superintendent, Richard Henry Pratt, the success of the tour wasn’t enough to compensate for her critical Atlantic Monthly articles. “But for those she has maligned, she would be a poor squaw in an Indian camp, probably married to some no-account Indian,” Pratt fumed privately. Articles critiquing Zitkála-Šá and her lack of gratitude began springing up in Carlisle’s publication Red Man.

Zitkála-Šá’s position at the CIIS became increasingly untenable. Instead of continuing her career there, she decided to return to the west and write about her heritage. The publishing house Ginn & Company asked for a collection of “Indian stories” for children, resulting in Old Indian Legends and American Indian Stories.

In May 1902, Zitkála-Šá married Raymond Bonnin, a classmate from White’s. A few months later, he got a job with the Office of Indian Affairs on the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in northeastern Utah. Zitkála-Šá recognized that moving to Utah meant sacrificing musical, and possibly literary, ambitions. But she also believed that she was in a position to better the lives of fellow Natives, and that any personal sacrifice would be worthwhile. No sooner had she arrived in Utah than she realized she was pregnant. On May 29, 1903, she gave birth to a son. She and Bonnin named the boy – their only child – Ohiya, or Winner.

Soon after Ohiya’s birth, Zitkála-Šá began teaching at the Uintah Boarding School at Whiterocks. There she came upon an abandoned collection of brass instruments, and soon Native schoolchildren were playing band concerts in the community, led by Zitkála-Šá herself.

The reservation was a place racked with poverty, disease, and corruption, and Zitkála-Šá’s life there was challenging. Much of her time was spent working and raising Ohiya; even more, it seems, was spent battling corruption and abuse originating with the American government. She sought refuge in religion, converting to Catholicism.

Interestingly, despite her passion for Native culture, that embrace of Catholicism led her to write disapprovingly of certain indigenous customs. But in 1910 she set any misgivings she had aside and attended a Ute performance of the Sun Dance. There she ran into a music teacher named William Hanson, a Mormon who had studied at Brigham Young University, and they got to talking about the meaning of the ceremony. Eventually Zitkála-Šá proposed a radical idea: they should co-write an opera about it.

The Sun Dance was a three or four day observance that originated with the Plains Algonquians in the early 1500s and subsequently spread from tribe to tribe. Tadeusz Lewandowski writes in Red Bird, Red Power: The Life and Legacy of Zitkála-Šá:

Generally, the Sun Dance features ceremonial dancing, singing, and music, all performed for onlookers who sit in a specially designated area. Individuals who choose to dance forego food and drink for the duration, and beforehand usually vow to fulfill a range of activities from leading a successful hunt to taking revenge on enemies in war.

The ceremony could include piercings:

Dancers endure piercings through the skin and sometimes under the muscle. Bison skulls may be attached to the piercings with tethers, in which case dancers drag them around the Mystery Hoop [a pole from a sacred tree] four times. The skin may tear open, signifying the most important part of the dancer’s sacrifice. Those who are pierced may alternatively be tied to the sacred tree, to then pull away until either the skin or the tether breaks. Pieces of flesh are subsequently given as offerings or signs of thanks. Ultimately, these days of deprivation, fasting, and bodily pain demonstrate that the dancer has offered his body, or himself, so that his prayers may be answered.

The United States government was horrified that such a custom existed. Ostensibly the concern was over its “barbaric, wild and heathenish” nature, but there were also political considerations. The Sun Dance often attracted thousands of Natives to one place, making the observance a ripe time and place for potential rebellion. In 1883, observance of the Sun Dance became illegal under U.S. law, and in 1904, the ban had to be reiterated. Nonetheless, Sun Dances were still observed, their political undertones lingering.

Perhaps this history explains why Zitkála-Šá – who was consistently attracted to subversive themes throughout her creative life – settled on the subject of a Sun Dance for an opera. P. Jane Hafer writes in “A Cultural Duet: Zitkála-Šá and The Sun Dance Opera”:

Rather than continuing as a trained Indian on exhibit, she may have been trying to assume artistic control with composition and direction of the opera and to present her own cultural viewpoint. The performance of the opera allowed her personal and cultural validation.

Zitkála-Šá and William Hanson spent two and a half years working on the opera. In his (admittedly unreliable) 1967 memoir, Hanson claimed that Zitkála-Šá would play Native chants and melodies on the violin while he improvised and notated at the piano. In his memoirs, Hanson ascribes Zitkála-Šá a bewildering variety of roles: “a full collaborator”, someone who “skeletoned the story”, a director, and even just an assistant. All of these descriptions would seem to be contradictions in terms. It is impossible to know exactly what role she played in The Sun Dance Opera‘s composition, but it seems it was a major one.

The Sun Dance’s plot revolves around a love triangle. The hero is Ohiya (Sioux and named after Zitkala’s ten-year-old son), the heroine Winona (who is Ute), and the villain Sweet Singer (who is Shoshone). Ohiya vows to court Winona by participating in the Sun Dance, even carving a flute to seduce her. The trickster Sweet Singer, on the other hand, tries to appeal directly to Winona’s father. Ohiya finishes the grueling dance, Winona falls in love with him, and Sweet Singer dies.

The opera contains a number of intriguing moments. One of the most striking is Ohiya’s initial “love chant” for Winona, which includes an element of improvisation. Since the main characters in the opera were played by whites, it seems likely that Zitkála-Šá trained them for their roles.

The first performances were held in Hanson’s hometown of Vernal, Utah. The project turned into a collaboration between whites and Natives. Classically trained white singers took on the leading roles, but the Utes were commissioned to create the costumes and share native songs and dance. The work was successful enough that it was revived and brought on tour. Occasionally Zitkála-Šá delivered what we might nowadays call a pre-concert talk, discussing the ritual.

Professor N. L. Nelson of Brigham Young University wrote a review for Salt Lake City’s Deseret News which was later excerpted in Musical America:

That our brothers and sisters of the desert have such a spiritual background to their lives, was a complete revelation to the writer, and makes him feel the need of meeting them on the plane of a nearer social and spiritual equality.

Of course, modern scholars are more hesitant to praise the work, for a variety of reasons. The depiction of the ceremony is not always accurate, and the mashup of an indigenous ceremony and European opera present serious problems for modern sensibilities.

It’s also difficult to pin down the score, as two dramatically different versions exist. In the words of Catherine Parsons Smith in her chapter of Opera Indigene: Re/presenting First Nations and Indigenous Cultures:

The first [version] is a rough piano-vocal version deposited in the US Copyright Office in 1912, about three months before the first production. This consists of a brief overture and twenty-three short numbers divided into three acts and five scenes. It includes some stage directions and the framework for a certain amount of spoken dialogue. No other copy of the 1913 version is known. The other score is a later revision, now at BYU, probably prepared for [a] 1938 New York revival. Its radical changes include added characters and events; the added magical “Love-Leaves,” slightly reminiscent of the love potion in Tristan und Isolde, are the most prominent example. Some numbers are eliminated, others are extensively recomposed, and still others are added. Sections performed by Ute men in the early production(s) are written out for later performers taking their roles. All these changes were made by Hanson.

Zitkála-Šá wasn’t a part of the 1938 revival. Tragically, by that time, she was very sick. Decades of frenetic advocacy for Native Americans had taken a physical toll. After composing The Sun Dance Opera, she had largely abandoned her musical pursuits in favor of writing and organizing, pushing for American citizenship for Natives and an end to government corruption. Zitkála-Šá passed away in January of 1938.

What exactly is the musical legacy of Zitkála-Šá? It’s a subject up for debate. But in an era when classical music lovers are wrestling with the buzzword diversity, it seems like a valuable exercise to look at her musical life and ascertain how her story and her voice might still speak to us today.

*

A huge shout-out to the patrons who make this series of articles on forgotten musical women possible! It wouldn’t happen without you. These articles come out every other Wednesday. If you want to support the series for as little as a dollar a month, click here.

If you want to learn more, here’s a list of sources:

Wikipedia page on Zitkála-Šá

Red Bird, Red Power: The Life and Legacy of Zitkala-Ša, by Tadeusz Lewandowski

“A Cultural Duet: Zitkala Ša And The Sun Dance Opera,” by P. Jane Hafen

“Composed and Produced in the American West, 1912-1913: Two Operatic Portrayals of First Nations Culture,” by Catherine Parsons Smith, Opera Indigene: Re/presenting First Nations and Indigenous Cultures

And here is an amazing video from Dovie Thomason, describing Zitkala-Ša and what her work means to her: