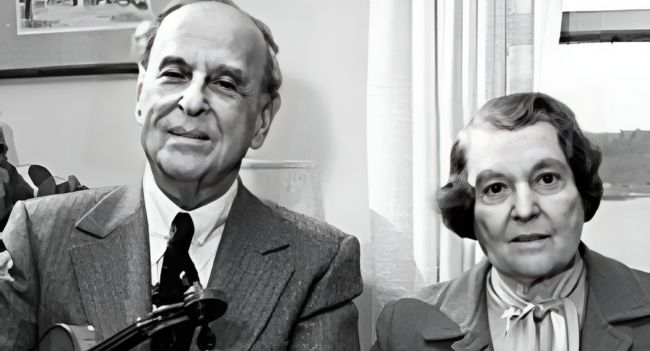

Few string-playing siblings have been as collectively spectacular as Joseph and Lillian Fuchs. Older brother Joseph was an exciting violinist with a fast vibrato, prodigious technique, and remarkable drive, whose career as soloist, concertmaster, and chamber musician made a major impact on American musical life for seventy years. (He gave his last Carnegie Hall recital at age ninety-three!) Younger sister Lillian was an indispensable force in viola history, whose ease and facility served as proof that that a diminutive woman could play viola as well as anyone, and whose rich tone helped establish a new sound ideal for the instrument, for anyone who may have thought of the viola as just a lower-pitched violin. Lillian was also a great advocate for violists playing Bach’s Cello Suites, becoming the first to record these works on her instrument, and doing much to establish the central role they play in its repertoire today. Together, Joseph and Lillian fostered the culture of chamber music in America, in particular elevating the violin-viola duo repertoire.

The Fuchs siblings were born in New York, children of an immigrant violin teacher from Poland. Joseph came into the world in 1899, and Lillian in 1902. (A younger brother Harry, born in 1908, would become principal cellist of the Cleveland Orchestra.) Joseph was a prodigy, studying from age six at what is now Juilliard, first with Louis Svećenski, violist of the famed Kneisel Quartet, and then with the quartet’s leader, Franz Kneisel, one of America’s premier violinists of the time. Joseph toured Europe playing the Brahms Concerto in 1919, made an acclaimed New York debut in 1920, and was appointed concertmaster of Cleveland in 1926, staying until 1940. For two years beginning in 1941, he was first violinist of the Primrose Quartet. Meanwhile he pursued a solo career, an endeavor highlighted by his 1947 premiere of the Lopatnikoff Concerto, 1959 recording of the Hindemith Concerto with Goossens and the London Symphony, and 1960 commissioning of the Piston Concerto.

Beginning in 1940, brother and sister began concertizing together on a regular basis. Both were important members of the Musicians’ Guild, a fixture of the New York chamber music scene in the ’40s and ’50s, and in 1953 they appeared together at the Casals Festival. They made no fewer than three joint recordings of Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante, and their performances of Mozart’s Duos inspired the composition of Martinů’s Madrigals, which are dedicated to them.

Luckily, much of the Fuchs’ wonderful work together can still be heard today. Their elegant Mozart Duo No. 2 in B-flat and imaginative Madrigals are most striking for their perfect unity of approach, in tempo and timing, articulation and phrasing. The Fuchs’ joint musicianship is also distinctly modern—no allowances need be made for their births and education in a bygone era. From the Casals Festival comes a Sinfonia Concertante, with Casals conducting, boasting the same satisfying compatibility, and a Mozart E-flat Divertimento with Paul Tortelier which, while occasionally over-propulsive, constitutes a marvelous meeting of three great musical minds.

Turning to solo efforts: Lillian Fuchs’ Bach Suites set an extremely high bar for all future recordings, on any instrument. (After hearing her Sixth Suite, Casals said the piece sounded better on viola.) Her Bach is simple yet subtle, disciplined yet free, the tone warm and unforced. In all, her Suites have aged far better than most Bach recordings from their era. Another treasure is the one-movement Sonata by Jacques de Menasce, written for her, and recorded with pianist Artur Balsam: her playing here is deeply affecting, soulful, sincere, and suffused with emotion.

Exceptional among Joseph’s recordings are his vibrant and convincing Hindemith, a thoroughly enjoyable Beethoven G major Sonata with Balsam, boasting perfect ensemble, succinct and logical phrasing, and a graceful negotiation of Beethoven’s many detailed markings, and a Beethoven “Ghost” Trio with Casals and Istomin featuring a striking largeness of musical conception—occasionally expressed in the form of singing from the great cellist.