By Sasha Margolis

When the thirty-year-old violinist Ginette Neveu perished in a plane crash in 1949, the music world experienced a deep sense of loss. In the nine years that followed, the grief was compounded by the deaths of three other extraordinarily gifted young violin stars: Josef Hassid (1923–50), Ossy Renardy (1920–53), and Julian Sitkovetsky (1925–58).

Sitkovetsky was, in the words of pianist Vladimir Ashkenazy, “a legendary violinist with a unique and demonic talent.” A native of Kiev, Sitkovetsky studied in Moscow with Abram Yampolsky, going on to win second prizes at the 1952 Wieniawski Competition and the 1955 Queen Elisabeth Competition. Yehudi Menuhin, a judge at the Queen Elisabeth, is said to have praised him as nothing less than “the greatest violinist I have ever heard.” David Oistrakh reportedly believed that, had his younger colleague lived longer, he would have surpassed Leonid Kogan and Oistrakh himself as the foremost Soviet violinist. His premature death was from lung cancer. He left as his widow pianist Bella Davidovich; their son is violinist Dmitry Sitkovetsky.

Sitkovetsky the father was, without a doubt, one of the great technicians in violin history—to which his recordings attest. His Ernst “Last Rose of Summer” is unlabored and assured, and his Paganini “Moses Fantasy” a model of ease. Among other Paganini works, “Le Streghe” is notable for a tone quality evoking something of Heifetz’s soprano sound, while “La Campanella,” played with piano, boasts a ricochet reaching improbable levels of percussiveness without losing an iota of pitch. Some of Sitkovetsky’s most winning lyrical playing can be heard in Moszkowski’s ”Guitarre” and a Glazunov Concerto performed with Kondrashin and the Moscow Symphony. Another stellar concerto recording is the Khachaturian, with the composer conducting the USSR State Radio Symphony: after a driven opening movement, the Andante sostenuto is painfully passionate.

While Sitkovetsky’s Paganini stands out for its assurance, Ossy Renardy’s is remarkable for its charm and naturalness. Paganini was the composer Renardy was most associated with. He sometimes included the complete Caprices on his recitals, and was also the first to record them in their entirety (in a version with piano accompaniment; Ruggiero Ricci would be the first to record the complete unaccompanied originals.)

Renardy was born in Vienna as Oskar Reiss. (He changed his name for enhanced musical appeal.) Incredibly, he seems to have been almost completely self-taught, yet made a debut with the Vienna Philharmonic at fourteen. After several U.S. tours in the late ’30s, he became an American citizen in 1943, and post-war played with most major U.S. orchestras. Conductor Charles Munch proclaimed: “There is only one word to describe him: perfection. He has everything—style, technique, and tone, combined in the most splendid manner.” Renardy died in a car accident in New Mexico at the age of 33.

The Paganini recordings he left behind, including the Caprices and “Le Streghe,” where his dazzling technical virtuosity is matched only by unfailing lyricism. His Sarasate “Romanza Andaluza” is imbued with natural charm, to which his “Zapateado” adds engaging verve. The energetic Zarzycki Mazurka and lyric Dvořák Ballade in D minor show off two sides of Renardy’s stylistic flexibility, ardent tone, and flowing musicality.

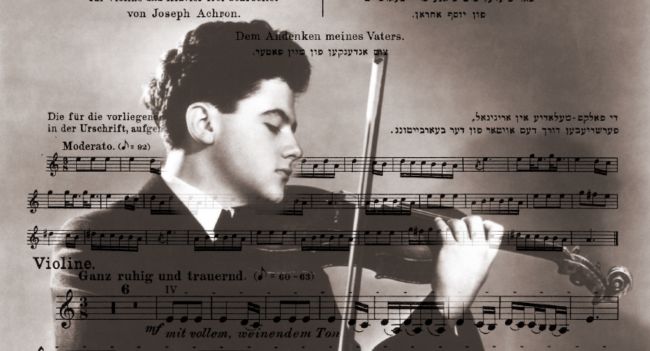

Josef Hassid, born in Suwałki, Poland, was among Carl Flesch’s countless gifted pupils. When Fritz Kreisler heard a young Josef play at Flesch’s house, he exclaimed, “A fiddler such as [X] is born every hundred years—one like Hassid, every two hundred.” X is widely assumed to have been Heifetz. The sixteen-year-old Hassid was in London when WWII broke out, and chose to stay. The next year, he made a London Philharmonic debut, creating a strong impression with his mature playing and boyish air. He later recorded eight short pieces accompanied by the great Gerald Moore, who recalled he “was at once struck by his (Hassid’s) genius.” Soon, however, Hassid began to suffer a mental breakdown, experiencing memory lapses and even becoming violent. At twenty, he was institutionalized, and just before his death—which may have been from meningitis—he underwent a lobotomy.

The scant eight pieces show what a musical loss his tragic breakdown and death was. Like Kreisler’s, Hassid’s sound and vibrato possess an intrinsic, riveting emotional intensity. His slides are mouthwatering, his double-stops gorgeous, and his trill enthralling. His interpretive strengths include poised rubato of the rarest kind and constant dynamic subtleties that give space and shape to the music. Of particular note are the perfect staccato inflections in Elgar’s “La Capricieuse,” the shaping and largeness of spirit in Dvořák’s Humoresque, the bewitching tone and thrilling impulsivity of Achron’s “Hebrew Melody,” the compelling architecture of Massenet’s “Thaïs,” and the endless variety of Iberian moods in Sarasate’s “Playera.”