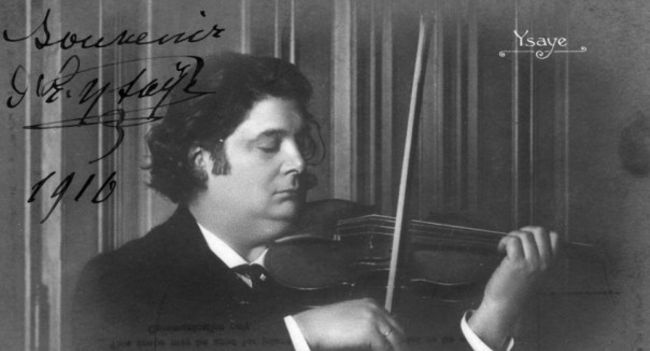

Eugène Ysaÿe broke the 19th-century Romantic virtuoso mould with a unique fusion of sleight-of-hand technique and profound musicianship.

Who was Eugène Ysaÿe?

A larger-than-life character in every respect, Eugène Ysaÿe mesmerised audiences with his devil-may-care spontaneity, which extended to changing fingerings and bowings as the mood inspired him in mid-performance. There was something of the subversive renegade about him – he could run temporal rings around insensitive conductors – yet he excelled at whatever he turned his hand to.

Ysaÿe’s impact as a teacher was incalculable. His pupils included Louis Persinger (Yehudi Menuhin’s first major tutor), Joshua Bell’s mentor Josef Gingold, composer Ernest Bloch and Nathan Milstein.

Carl Flesch – whose pupils included Henryk Szeryng and Ida Haendel – considered Ysaÿe ‘the most outstanding and individual violinist I have heard in my life,’ while celebrated French virtuoso Jacques Thibaud felt he was ‘the great apostle of the truly musical’.

Ysaÿe was also an outstanding chamber musician – the original Quatuor Ysaÿe made its debut in 1888 – and following the creation of the Orchestre des Concerts Ysaÿe in 1895 proved to be a first-rate conductor. Of course, he was also a composer.

Although much of his music (amounting to some 35 opuses) appeared in print, he himself remained unconvinced as to its true worth. Remarkably, not one of his eight violin concertos was published over the course of his lifetime, yet they trace a fascinating creative journey that saw Ysaÿe develop from a poetic dreamer in the Schumann tradition into a post-Wagnerian sensualist.

When was Ysaÿe born?

Born on 16 July 1858 in Liège, Belgium, the ‘King of the Violin’ (as Ysaÿe became popularly known) made steady rather than spectacular progress at first. Indeed, following lessons with his father and playing in several large ensembles, it looked as though he might become part of the orchestral fraternity, especially after being appointed concert-master of Berlin’s Bilse Kapelle – essentially the Philharmonic in embryo.

When did Ysaÿe start to become known as a violinist?

This was despite having had lessons with two of the most famous violinist-composers of the day – Henri Vieuxtemps and Henryk Wieniawski. Yet such was his exceptional ability, word soon got around and with the keen support of violinist-composer Joseph Joachim and pianist-composer-conductor Anton Rubinstein, Ysaÿe began touring as a soloist.

He first made his mark with his 1883 Paris debut, performing Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole and Saint-Saëns’s Introduction and Rondo capriccioso, both scintillating showpieces made indelible by Ysaÿe’s interpretative zeal and beguiling phrasing.

However, the natural flair that was such a vital part of his artistic personality would prove something of a liability in later life. Part of the problem was his unconventional bow-hold – a firm three-finger grip, with the little finger only rarely touching the stick – which led gradually to an unsteady bowing arm and made legato playing increasingly challenging.

As so often with high-risk players dependent on the inspiration of the moment, Ysaÿe also began suffering from bouts of pre-concert nerves. At times he became literally paralysed with fear, the fingers of his left-hand rendered virtually useless. ‘The fingers are weak and the bow unsteady,’ he despaired in a letter of 1909. ‘I am going through one of those pessimistic crises, nerve-wracking and terribly sad.’ His predilection for generous quantities of food and liqueur also inevitably began to take its toll.

During this period, Ysaÿe’s creative output continued to be dominated by shorter works for soloist and orchestra and piano-accompanied miniatures. Yet such innocent, salonesque titles as Poème nocturne (one in a series of eight poèmes for soloist and orchestra) disguised a highly personal idiom which demonstrates an unexpectedly keen awareness of contemporary trends – especially for one who claimed to be out of step with the ‘modern’ age. His Poème élégiaque of 1895, for example, provided the vital catalyst for the exotic chromaticisms that pepper Chausson’s famous Poème for violin and orchestra, dedicated to Ysaÿe in grateful appreciation.

Other composer friends who dedicated important works to Ysaÿe included Debussy – his G minor String Quartet, premiered by the Quatuor Ysaÿe in 1893 – and Franck, whose indelible Violin Sonata was composed as a wedding present. During the Sonata’s 1886 premiere, dusk began to fall and as no artificial lighting was allowed in the museum where they were performing, Ysaÿe and his accompanist Léontine Bordes-Pène played the remaining three movements from memory in the near-darkness!

Who did Ysaÿe marry?

In 1886 Ysaÿe married Louise Bourdeau de Courtrai.On the morning of his marriage, César Franck gave him his new Violin Sonata as a wedding present. He plays it that same day.

During the 1890s and 1900s, he attracted legions of devoted admirers throughout Western Europe (Britain especially) and Russia, including Rachmaninov, who was himself on the verge of international acclaim with his Second Piano Concerto.

Ysaÿe’s harmonic language became increasingly languorous during this period, emitting a French musical perfume as intoxicating as those being developed by Fauré, Debussy and Ravel. This was felt particularly in a series of works for violin and orchestra with such evocative titles as Au rouet (‘To the Spinning-Wheel’), Chant d’hiver (‘Song of Winter’), Les neiges d’antan (‘The Snows of Yesteryear’) and Extase (‘Ecstasy’).

These were the years of Ysaÿe’s greatest fame as a violinist. Having acquired a magnificent 1740 Guarnerius del Gesù, his tone became more rounded and thrilling in its projection. This, coupled with his unusually fast vibrato, leant his interpretations an exciting, edge-of-the-seat quality. Sir Henry Wood, founder of the Proms, spoke for a whole generation when he enthused that ‘having accompanied all the great violinists in the world during the past 50 years, of all of them Ysaÿe impressed me most. He seemed to get more colour out of a violin than any of his contemporaries… I learned more in my early days from this great man than all other [soloists] put together.’

By the time Ysaÿe gave a legendary 1912 performance of the Elgar concerto in Berlin under Arthur Nikisch, he was at the peak of his fame. Among his many younger admirers in the audience that night was Mischa Elman, Fritz Kreisler (who had premiered the concerto under Elgar’s direction just two years previously) and Carl Flesch. After the concert Ysaÿe joined them for an impromptu soirée during which all four violin legends played

for each other simply for pleasure.

Later that year Ysaÿe (who loathed recording) was persuaded to cut a series of discs between December 1912 and January 1913 that represents the bulk of his slender discography. Through the inevitable surface noise and relatively primitive recording technology of the early 20th century, one can still sense the presence of a player blessed with astonishing tonal command and musical insight.

The unpredictability of the political situation in Europe – his three sons were conscripted into the army during World War I – was increasingly reflected in his own playing. Plagued by bowing-arm tremors and occasional memory lapses, by the time he fled Belgium for England and the US with his wife in 1914, he was considering a change of career to conducting. Yet he continued giving recitals, both in London and in the US, where he was offered the conductorship of the Cincinnati Orchestra from 1918-22.

Like Rachmaninov (at least initially), who arrived in America from Europe at much the same time, Ysaÿe’s creative drive flickered rather than surged on ‘foreign’ soil. Being sensitive to both time and place, despite the warm welcome he was afforded, composing became less of an imperative away from the immediate sources of his inspiration.

When he returned to Europe in 1922, attempts to revive his solo career were welcomed with great affection, but more perhaps for the man than his actual playing. As was the case with Menuhin half-a-century later, despite the occasional technical frailty people still flocked to hear the great man perform in the hope of catching the ‘King’ at his incandescent best.

What is Ysaÿe’s most famous work?

Ysaÿe took his final bow as a performer with a 1927 concert in Barcelona. Yet just as his executant powers seemed to be waning, in 1924 his creative facility hit an entirely new level with a set of six solo violin sonatas, composed in homage to Johann Sebastian Bach, whose solo sonatas and partitas Ysaÿe had heard played matchlessly by Joseph Szigeti.

Each one is dedicated to a younger virtuoso in the violin firmament, as though Ysaÿe intended them as a musical gift to the next generation. The first four were written for established virtuosos – Szigeti, Thibaud, Enescu and Kreisler – while the final pair went to two highly gifted players on the verge of celebrity: former pupil Matthieu Crickboom (the original second violin in Ysaÿe’s own quartet) and Manuel Quiroga, whose career was cut tragically short in 1937 by a traffic accident in New York.

Requiring a high level of virtuosity, they later become his best-known works.

When did Ysaÿe die?

But by now time was running out for Ysaÿe. Concerns regarding his already fragile health – he suffered from diabetes – were further exacerbated when in 1929 he had to have his right foot amputated. Undeterred, he began conducting again, determined to lead the premiere of his recently composed one-act opera, Piére li houïeu (‘Peter the Miner’), the only work of its kind cast in the Walloon language. In the event the effort proved too much: he collapsed during the first rehearsal, although he managed to attend the premiere two weeks before his death on 12 May 1931 aged 72.

When was the Eugène Ysaÿe Competition launched?

In recognition of Ysaÿe’s remarkable achievements, Queen Elizabeth of Belgium inaugurated the first Eugène Ysaÿe Competition in 1937, which was won by David Oistrakh. Sixteen years later, in the 1953 movie Tonight We Sing (celebrating the life of impresario Sol Hurok), Ysaÿe was played by none other than Isaac Stern. The ‘King’ could hardly have wished for two finer players to carry his mantle into the second half of the 20th century.

What most impresses one who meets Ysaye and talks with him for the first time is the mental breadth and vision of the man; his kindness and amiability; his utter lack of small vanity. When the writer first called on him in New York with a note of introduction from his friend and admirer Adolfo Betti, and later at Scarsdale where, in company with his friend Thibaud, he was dividing his time between music and tennis, Ysaye made him entirely at home, and willingly talked of his art and its ideals. In reply to some questions anent his own study years, he said:

“Strange to say, my father was my very first teacher—it is not often the case. I studied with him until I went to the Liège Conservatory in 1867, where I won a second prize, sharing it with Ovide Musin, for playing Viotti’s 22d Concerto. Then I had lessons from Wieniawski in Brussels and studied two years with Vieuxtemps in Paris. Vieuxtemps was a paralytic when I came to him; yet a wonderful teacher, though he could no longer play. And I was already a concertizing artist when I met him. He was a very great man, the grandeur of whose tradition lives in the whole ‘romantic school’ of violin playing. Look at his seven concertos—of course they are written with an eye to effect, from the virtuoso’s standpoint, yet how firmly and solidly they are built up! How interesting is their working-out: and the orchestral score is far more than a mere accompaniment. As regards virtuose effect only Paganini’s music compares with his, and Paganini, of course, did not play it as it is now played. In wealth of technical development, in true musical expressiveness Vieuxtemps is a master. A proof is the fact that his works have endured forty to fifty years, a long life for compositions.

Ysaye’s Repertory

Ysaye spoke of Vieuxtemps’s repertory—only he did not call it that: he spoke of the Vieuxtemps compositions and of Vieuxtemps himself. “Vieuxtemps wrote in the grand style; his music is always rich and sonorous. If his violin is really to sound, the violinist must play Vieuxtemps, just as the ‘cellist plays Servais. You know, in the Catholic Church, at Vespers, whenever God’s name is spoken, we bow the head. And Wieniawski would always bow his head when he said: ‘Vieuxtemps is the master of us all!’

The Tools of Violin Mastery

“With regard to mechanism,” Ysaye continued, “at the present day the tools of violin mastery, of expression, technic, mechanism, are far more necessary than in days gone by. In fact they are indispensable, if the spirit is to express itself without restraint. And the greater mechanical command one has the less noticeable it becomes. All that suggests effort, awkwardness, difficulty, repels the listener, who more than anything else delights in a singing violin tone. Vieuxtemps often said: Pas de trait pour le trait—chantez, chantez! (Not runs for the sake of runs—sing, sing!)

“When I said that the string instruments, including the violin, subsist in a measure on the heritage transmitted by the masters of the past, I spoke with special regard to technic. Since Vieuxtemps there has been hardly one new passage written for the violin; and this has retarded the development of its technic. In the case of the piano, men like Godowsky have created a new technic for their instrument; but although Saint-Saëns, Bruch, Lalo and others have in their works endowed the violin with much beautiful music, music itself was their first concern, and not music for the violin. There are no more concertos written for the solo flute, trombone, etc.—as a result there is no new technical material added to the resources of these instruments.

“In the days of Viotti and Rode the harmonic possibilities were more limited—they had only a few chords, and hardly any chords of the ninth. But now harmonic material for the development of a new violin technic is there: I have some violin studies, in ms., which I may publish some day, devoted to that end. I am always somewhat hesitant about publishing—there are many things I might publish, but I have seen so much brought out that was banal, poor, unworthy, that I have always been inclined to mistrust the value of my own creations rather than fall into the same error. We have the scale of Debussy and his successors to draw upon, their new chords and successions of fourths and fifths—for new technical formulas are always evolved out of and follow after new harmonic discoveries—though there is as yet no violin method which gives a fingering for the whole-tone scale. Perhaps we will have to wait until Kreisler or I will have written one which makes plain the new flowering of technical beauty and esthetic development which it brings the violin.

Violin Mastery

“When I take the whole history of the violin into account I feel that the true inwardness of ‘Violin Mastery’ is best expressed by a kind of threefold group of great artists. First, in the order of romantic expression, we have a trinity made up of Corelli, Viotti and Vieuxtemps. Then there is a trinity of mechanical perfection, composed of Locatelli, Tartini and Paganini or, a more modern equivalent, César Thomson, Kubelik and Burmeister. And, finally, what I might call in the order of lyric expression, a quartet comprising Ysaye, Thibaud, Mischa Elman and Sametini of Chicago, the last-named a wonderfully fine artist of the lyric or singing type. Of course there are qualifications to be made. Locatelli was not altogether an exponent of technic. And many other fine artists besides those mentioned share the characteristics of those in the various groups. Yet, speaking in a general way, I believe that these groups of attainment might be said to sum up what ‘Violin Mastery’ really is. And a violin master? He must be a violinist, a thinker, a poet, a human being, he must have known hope, love, passion and despair, he must have run the gamut of the emotions in order to express them all in his playing. He must play his violin as Pan played his flute!”

In conclusion Ysaye sounded a note of warning for the too ambitious young student and player. “If Art is to progress, the technical and mechanical element must not, of course, be neglected. But a boy of eighteen cannot expect to express that to which the serious student of thirty, the man who has actually lived, can give voice. If the violinist’s art is truly a great art, it cannot come to fruition in the artist’s ‘teens. His accomplishment then is no more than a promise—a promise which finds its realization in and by life itself. Yet Americans have the brains as well as the spiritual endowment necessary to understand and appreciate beauty in a high degree. They can already point with pride to violinists who emphatically deserve to be called artists, and another quarter-century of artistic striving may well bring them into the front rank of violinistic achievement!”