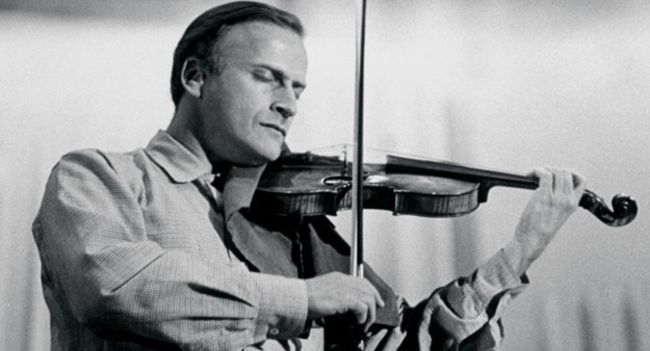

There’s never been another violinist like the young Yehudi Menuhin. As an adolescent, gifted with boundless talent and utter unselfconsciousness, Menuhin scaled the most exalted artistic heights, producing tones of unparalleled purity and nobility from his fiddle, and drawing listeners into his total communion with the music he was playing. “Now I know there is a God in heaven,” exclaimed Albert Einstein when he heard him. And conductor Bruno Walter said, “He was a child, and yet he was a man and a great artist.” Some time around the age of twenty-five, Menuhin suffered a crisis in his playing, losing his magical absence of self-awareness and devolving into a less consistently great performer. But even then, he remained an extraordinary artist, who continued to make stellar recordings.

Menuhin was born in New York in 1916, and spent his childhood in San Francisco, where his principal teacher was Louis Persinger. He started performing early, striking audiences at once as more than just a technical whiz. At ten, he performed Lalo’s Symphonie Espagnole with the San Francisco Symphony. He then departed to Europe for further studies with George Enescu, a musician of extraordinary breadth and imagination. At thirteen, he performed concerti of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms in one concert with Walter and the Berlin Philharmonic. By fifteen or so, he had blossomed into as great a violinist as has existed, blessed with fantastic facility, unfettered spontaneity, sophisticated rhythmic subtlety, understanding beyond his years, openhearted communicativeness, and a tone that was at once earthy and innocent and intense. These qualities catapulted him into the company of Kreisler and Heifetz as one of the world’s most in-demand and well-compensated violinists.

Many explanations have been offered for the decline that Menuhin experienced some time around 1940. Perhaps it was that a faulty technique ignored by indulgent teachers caught up to him, or that a too consistently high right elbow led to an uncontrollable bow tremor. Maybe a sudden onset of adult self-awareness destroyed his rare instinctiveness, or else, playing too many concerts for troops during WWII ravaged his bow arm. It has also been suggested that its root was repressed anger, marriage trouble, or an undiagnosed neurological condition. In any case, Menuhin experienced a crisis.

All this is well-documented on Menuhin’s recordings, which span his career. An age eleven, Menuhin shows off his precocious virtuosity in Ries’ “La Capricciosa,” and at age twelve, his early ability to transmit deep feeling is showcased in Samazeuilh’s “Chant d’espagne.” Simply incredible are his musical conviction and intensity of sound in the Elgar Concerto, recorded at sixteen with the composer conducting London. A Falla “Danse espagnole” from the same period plays reaches heights of style and sophistication, while Wieniawski’s “Scherzo tarentelle” is stunning for its virtuosity and effortless high-register playing.

Menuhin recorded Symphonie Espagnole at seventeen with Enescu and the Paris Symphony. The performance is an incredible display of vocal violin-playing, with startingly deft position changes and slides as natural as breathing. A Paganini Concerto recorded a year later with Monteux and Paris captures the piece’s operatic essence as perhaps no other rendition has. Soon after, Menuhin put forth a lightning-quick Bazzini “Ronde des Lutins,” perhaps intended to give Heifetz a run for his money.

Advertisement

No one has played Sarasate better than Menuhin did at nineteen: his “Caprice Basque,” “Habanera,” and “Zapateado” crackle and sparkle and give vivid color to every change of mood and register. The same year, he recorded Enescu’s Third Sonata with his fifteen-year-old sister Hephzibah, a lifelong musical partner. Yehudi’s spontaneous timing and timbral range show his spiritual connection with the composer. And a Mozart G Major Concerto with Enescu and Paris displays his sheer communicativeness. In 1937, Menuhin became involved in an intrigue-filled international race to debut the rediscovered Schumann Concerto. His 1938 recording with Barbirolli and the New York Philharmonic shows the piece to its best advantage. Just afterward, Menuhin rounded out the first, youthful phase of his recording career with a Schumann-Kreisler Romance unsurpassed in tonal beauty, and an impulsive, impassioned Granados “Andaluza.”

The adult Menuhin’s qualities lent themselves beautifully to the sonata repertoire. Joining Hephzibah for the Franck, he plays with utter naturalness, finding moments of deepest repose amidst phrases planned with phenomenal foresight. Bartók was a fan of the siblings’ youthful playing of his First Sonata. Their later, rhapsodic recording shows why. Menuhin’s Brahms G major and A major sonatas with Louis Kentner (his wife’s brother-in-law) are full of poignant, personalized gestures which in no way interfere with the musicians’ largeness of conception and brilliant pacing and shaping. Among the most profound interpretations of the Beethoven Concerto is Menuhin’s with Furtwängler and the Lucerne Festival Orchestra. An impassioned delight is Vieuxtemps’ Fourth Concerto with Susskind and the Philharmonia. And no collection of Menuhin’s later recordings would be complete without some of his fascinating collaborations with sitarist Ravi Shankar, testaments to his limitless open-mindedness and pure love for music.